Cities are not receiving the funding they need to adapt to the impacts of climate change. By leveraging their balance sheets and technical expertise, multilateral development banks can be a cornerstone in attracting the financing cities in low- and middle-income countries need to achieve their climate action plans.

As we take stock of the outcomes of the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28) and prepare to take necessary further action, the critical role of cities in tackling the climate crisis has never been more recognized.

In a first-of-its-kind collaboration, the COP 28 Presidency co-hosted the first Local Climate Action Summit with Bloomberg Philanthropies. The gathering brought together hundreds of local leaders to highlight their integral contribution to reducing emissions and managing climate risks and launched a nationwide initiative to accelerate climate action.

Still, serious challenges remain in financing urban climate action. Cities consume 78% of global energy consumption and produce more than 60% of total greenhouse gas emissions. Low- and middle-income countries face significant climate risks, including extreme weather events. As a result, cities will represent nearly $30 trillion in climate investment opportunities by 2030. More than 13,000 people have committed to urban climate investments through the Global Covenant of Mayors.

Despite the huge potential, there is a significant gap in climate investment, with global cities receiving only 7-8% of the funding they need. Cities face significant barriers, including bad credit, fiscal constraints and gaps in institutional capacity, hindering their ability to access funding and implement sustainable programs.

Multilateral development banks play a vital role in advancing climate finance for cities, leveraging their large balance sheets and technical expertise. By working with governments, multilateral development banks can create an environment conducive to investment in urban climate plans. Ongoing reform efforts at the multilateral development banks provide an opportunity for more coordinated action, providing low-hanging fruit for effectively accelerating climate goals.

During the 28th session of the Conference of the Parties, the major multilateral development banks issued a joint statement pledging to improve climate and development integration, emphasizing increased climate finance, enhanced measurement of results, and enhanced cooperation at the country level.

The following year, the need for MDB reform was incorporated into the final COP text. The call is clear: multilateral development banks must collaborate more closely to have a more substantial impact and continue to expand their climate finance. However, as important documents such as the World Bank’s “Evolution Roadmap” demonstrate, urban needs have been ignored in MDB reform discussions.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s recognition of the importance of local access to development financing signals a potential shift in considering urban needs in ongoing reform conversations.

However, a key challenge now faces: how can multilateral development banks translate these insights into practical progress in sustainable urban development? A new paper from the Urban Climate Finance Leadership Alliance provides some answers.

More funding and reporting are needed, especially on urban adaptation

Multilateral development banks are actively addressing urban climate finance challenges through specialized practice areas and large climate investment portfolios. Initiatives such as the Urban Gap Facility of the European Investment Bank and the World Bank and the Urban and Municipal Development Facility of the African Development Bank provide technical assistance for project preparation.

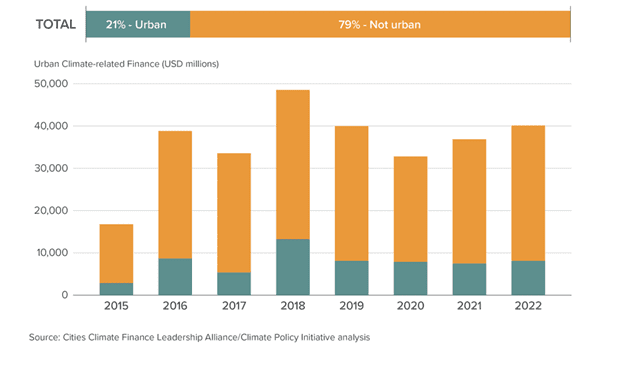

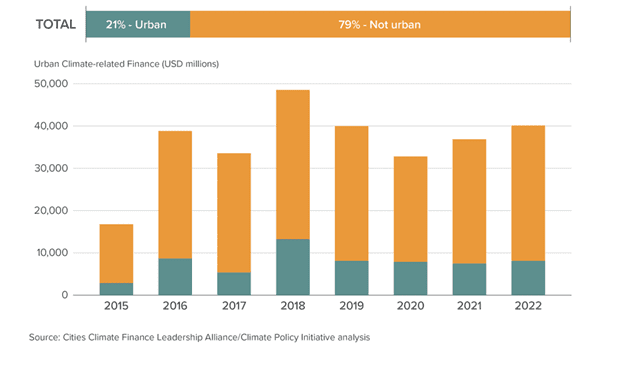

Research from the Leadership Alliance on Cities Climate Finance shows that 21% of climate-related finance provided by multilateral development banks to low- and middle-income countries between 2015 and 2022 was used to support urban programs. Despite increasing urbanization, climate-related financing in cities tracked by multilateral development banks has remained relatively stable.

Cities' share of climate-related financing provided by multilateral development banks to low- and middle-income countries, 2015-2022.

As multilateral development banks undergo reshaping, there is a need to increase urban climate finance, especially adaptation finance in high-need areas. Urban mitigation efforts currently receive more funding than adaptation, with climate-vulnerable regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa receiving the least urban climate-related investments.

It is important that multilateral development banks report on cities’ share of their climate finance to monitor progress. While some multilateral development banks monitor this internally, inconsistent definitions hinder coordinated and transparent reporting.

“COP28 is not the finale of MDB reform, but the beginning of the bank’s collaboration with stakeholders to develop solid plans to increase climate investment in cities.”

Changes in MDB’s operating model

City leaders find it challenging to obtain MDB financing due to the current project-focused approach that prioritizes large-scale infrastructure projects.

Investments in smaller cities tend to fall below financing thresholds, while sovereign guarantee requirements create difficulties amid political tensions between national and local governments. Small and medium-sized cities may have difficulty affording hard currency financing from multilateral development banks.

To strengthen urban climate finance, multilateral development banks should take a more programmatic approach, as evidenced by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Green Cities Programme. The model supports cities to co-develop climate action plans, promoting coordination and efficiency in meeting different city needs.

While not all multilateral development banks provide funding directly to cities, they can leverage intermediaries such as national development banks and local commercial banks to support municipalities, infrastructure projects and companies involved in urban climate solutions.

Through capacity building by multilateral development banks, these local institutions can contribute to systemic urban climate transformation at the national level.

Join forces to achieve scale

COP28 is not the grand finale of multilateral development bank reform, but the beginning of the bank’s collaboration with national governments, local leaders, the private sector and other stakeholders to develop solid plans to increase climate investment in cities. Multilateral development banks cannot address urban climate challenges alone, but together with other actors they can be a driving force.

A good starting point for multilateral development banks would be to work more closely together, building on each other's strengths in overlapping geographies and business units. For example, multilateral development banks could collaborate to develop national sector platforms to scale up more coordinated urban climate investment pipelines.

As implementation continues apace after COP 28, urban climate finance should be prioritized as a strategic element of multilateral development bank reform. Strengthening the capacity of cities in low- and middle-income countries to cope with the climate crisis is necessary to achieve global climate goals, and multilateral development banks can play a key role in managing this process.

The good news is that MDBs are not starting from scratch. While innovative plans and fit-for-purpose financial instruments are needed, much can be achieved by building on existing city initiatives and leveraging each other's platforms. The blueprint for change is already in place, calling on multilateral development banks to seize this opportunity in 2024.