Today's four-day forecast is as accurate as the one-day forecast 30 years ago.

Weather forecasts are generally seen as a good thing. This is useful when planning a Sunday BBQ, or when we're wondering if we'll need an umbrella that day. But in many ways, weather forecasts are absolutely crucial: they can be a matter of life or death.

Accurate forecasts can save lives by providing early warning of storms, heat waves and disasters. Farmers use them for agricultural management, which can result in poor or bumper harvests. Grid operators rely on accurate forecasts of temperatures for heating and cooling demand, and how much energy they will get from wind and solar farms. Pilots and sailors need them to safely carry people across oceans. Accurate information about future weather is often crucial.

In this article, I look at the progress that has been made over time and the global inequalities that need to be eliminated to protect lives and livelihoods around the world.

Weather forecasting has come a long way. In 650 BC, the Babylonians attempted to predict weather patterns based on cloud patterns and movements. Three centuries later, Aristotle wrote meteorological, discusses how phenomena such as rain, hail, hurricanes, and lightning are formed. Although much of it was proven wrong, it represented one of the first attempts to explain in detail how weather works.

It was not until 1859 that the Met Office Published the first Shipping weather forecast. Two years later, it made its weather forecast public for the first time. While meteorological measurements have improved over time, forecasts have changed dramatically with the use of computer numerical models. This did not begin until a century later, in the 1960s.

Since then, forecasts have improved significantly. We can see this through a range of measurements and from different national meteorological organizations.

Met Office explain Its four-day forecasts are now as accurate as their one-day forecasts were 30 years ago.

Forecasts for the U.S. are also getting better. We can see this in some of the most important predictions: predictions of hurricanes.

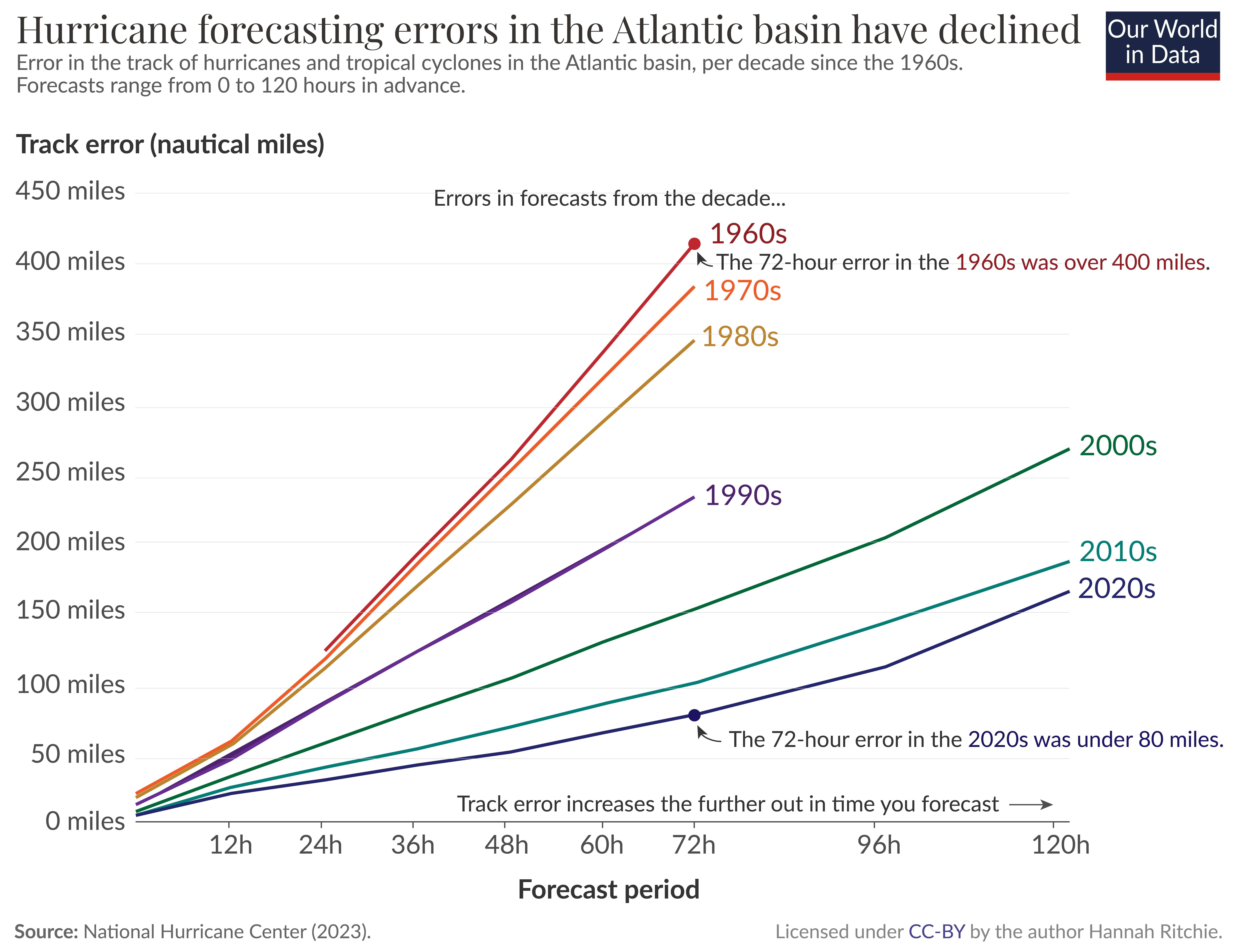

National Hurricane Center publish data About “Trajectory Error” of Hurricanes and Cyclones – Error Where A hurricane is coming. As shown below, from the 1960s.

Each line represents the error of the forecast for a different time period ahead. For example, 12 hours before hit, up to 120 hours (or 5 days) before hit.

We can see that this tracking error – especially in long-term forecasts – has reduced a lot over time. In the 1970s, the error in 48-hour forecasts was between 200 and 400 nautical miles; today the distance is about 50 nautical miles.

We can display the same data in another way. In the graph below, each line represents the average error for each decade. The horizontal axis is the forecast period, again extending from 0 hours to 120 hours.

The 72-hour error in the 1960s and 1970s was more than 400 nautical miles. Today, the distance is less than 80 miles.

Meteorologists can now make fairly accurate predictions of where hurricanes will hit three to four days in advance, allowing cities and communities to prepare while preventing unnecessary evacuations that might have been implemented in the past.

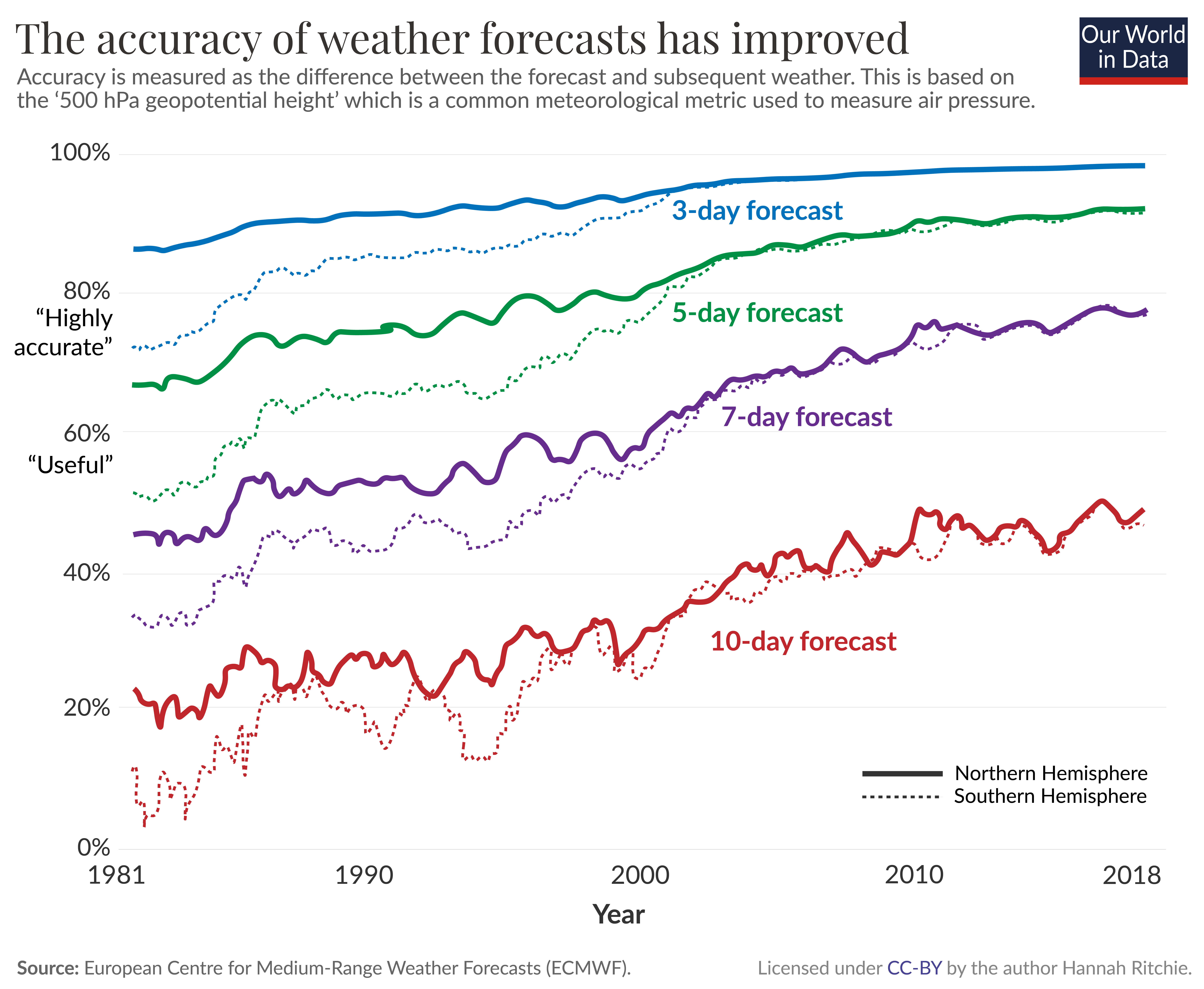

this European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) produces global numerical weather models. While national weather agencies use higher-resolution processing to obtain local forecasts, these global models provide important input to these systems.

ECMWF publishes its analysis of errors over time. As shown below.1 It shows the difference between the forecast and the actual weather forecast for 3, 5, 7 and 10 days ahead. The indicator used here is “500 hPa geopotential height”, a commonly used meteorological measurement method of barometric pressure (which determines weather patterns).

The solid line represents the Northern Hemisphere and the dashed line represents the Southern Hemisphere.

The three-day forecast (shown in blue) has been reasonably accurate since the 1980s and continues to get better over time. Today, the accuracy rate is about 97%.

The biggest improvement we see is the longer time frame. By the early 2000s, five-day forecasts were already “highly accurate,” and today seven-day forecasts are reaching that threshold as well. The 10-day forecast hasn't quite materialized yet, but it's getting better.

some key developments explain these improvements.2

The first big change is that the data has improved. Wider and higher-resolution observations can be used as input to weather models. This is because we have more and better satellite data, and ground-based stations cover more areas of the world with greater density. The accuracy of these instruments has also increased.

These observations are then fed into numerical prediction models to predict weather. This brings us to our next two developments. The computers that run these models have gotten faster. More speed is crucial: the Met Office now divides the world into smaller and smaller grids. While they once modeled the world using 90-kilometer-wide squares, that has now been reduced to a 1.5-kilometer-wide grid. This means more calculations are needed to obtain this high-resolution map. The method of converting observations into model outputs has also been improved. We have moved from a very simple vision of the world to approaches that capture the complexity of these systems in detail.

The final key factor is how these predictions are communicated. Not so long ago, you could only get daily updates in the daily newspaper. With the rise of radio and television, you probably receive a few notifications every day. Now we can get minute-by-minute updates online or on our smartphones.

At home in Scotland, I can open the app on my phone and get a reasonably accurate 5-day weather forecast in seconds. Unfortunately, not everyone has access to information of this quality. Weather forecasts vary widely around the world, as do the gaps between rich and poor.

As researchers Manuel Linsenmeier and Jeffrey Shrader report in a report recent papers7-day forecasts in rich countries may be more accurate than 1-day forecasts in some low-income countries.3

Although projections across income levels across the country have improved over time, the quality gap is nearly as wide today as it was in the 1980s.

There are several reasons for this. First, there are far fewer land-based instruments and radiosondes to measure meteorological data in poorer countries. Second, reports are reported much less frequently.

This is not surprising when we look at the amount of money spent on weather and climate information. exist a dissertation Published in scienceLucien Georgeson, Mark Maslin and Martin Posino examine differences in spending across income groups.4 This includes private and public expenditures on commercial products within the definition of “weather and climate information services”.

This is shown as expenditure per personand the ratio of expenditures to gross domestic product (GDP) in the table below.

Low-income countries spend 15 to 20 times less per capita than high-income countries. But given the size of their economies, they actually spent more As part of GDP.

This gap is a problem. 60% of workers in low-income countries engaged in agriculture, arguably the most weather-dependent sector. most are small-scale farmersthey tend to be very poor.

Accurate weather forecasts help farmers make better decisions. They can get information about the best time to plant crops. They know in advance when irrigation is most needed, or when fertilizer may be at risk of being washed away. They can receive alerts about pest and disease outbreaks so they can protect crops when an attack strikes, or save pesticides when the risk is lower. This means that if they have access to accurate weather forecasts, they can make the most efficient use of their precious resources. Good weather forecasts are vital for the world's poorest people.

They are also critical in protecting against hurricanes, heat waves, floods and storm surges. Having accurate forecasts days in advance allows cities and communities to prepare. Housing can be protected and emergency services can be on standby to aid recovery.

But accurate predictions alone won’t solve the problem: Forecasts are only useful if they are communicated to people so they can react. Many of the worst disasters of the past few decades be accurately predicted Advance time. A common failure is poor communication.5

Improving forecasting is fundamental. But these also need to be incorporated into effective early warning systems. world meteorological organization estimate About a third of the world's countries – mainly the poorest – do not have these.

After huge improvements in recent decades, we take good weather forecasting and dissemination for granted in much of the world. Making it available to everyone will make a difference.

This will become even more important as climate change increases the risk of weather-related disasters. Ultimately, it is the poorest and most vulnerable who will suffer the worst consequences. Better predictions are key to good adaptation to climate change.

Appropriate investment and financial support are critical to closing the gap.

There are also emerging technologies that can speed up the process. A recent papers Published in nature recorded a new Artificial Intelligence (AI) The system – Pangu Weather – can make forecasts 10,000 times more accurate (or better) than leading weather agencies, and 10,000 times faster.6 It was trained on 39 years of historical material. The speed of these forecasts will make them significantly less expensive to run and could provide better results for countries with limited budgets.

Faster, more efficient technology can also fill gaps where land-based weather stations are unavailable. Sensor-carrying drones can survey specific areas to build higher-resolution maps. Mobile technology can quickly disseminate this information by turning it into predictions in a cheaper and more efficient way. Some companies have sent messages to farmers in low-income countries advising them on the best times to plant their crops.

This innovation is critical to improving countries’ ability to cope with today’s weather. But it's also important in a world where weather may become more extreme.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Max Roser and Edouard Mathieu for their valuable feedback and comments on this article.

cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on the work of many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying source. This article may be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2024) - “Weather forecasts have become much more accurate; we now need to make them available to everyone” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/weather-forecasts' [Online Resource]BibTeX citations

@article{owid-weather-forecasts,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {Weather forecasts have become much more accurate; we now need to make them available to everyone},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/weather-forecasts}

}Feel free to reuse this work

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are fully open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the right to use, distribute and reproduce the content in any medium, provided the source and author are credited.

Material generated by third parties and provided by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms of the original third party author. We will always give credit to the original source of material in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third party material before using and redistributing it.

All of our graphics can be embedded into any site.