Computer models predict that a large tropical wave approaching the Lesser Antilles is currently encountering too much dry air to develop, but that it will encounter wetter and more favorable conditions for development near the Bahamas this weekend.

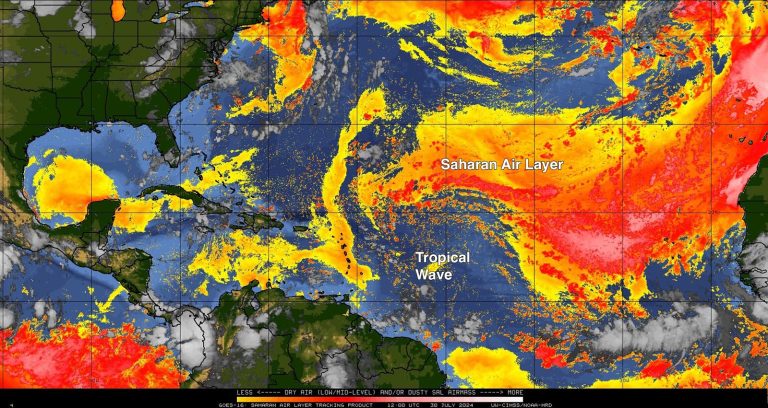

The tropical wave, which is not yet organized enough to be awarded an “investment” designation by the National Hurricane Center, was centered hundreds of miles east of the Lesser Antilles on Tuesday morning and was heading northwest at about 15 mph. Move west. Satellite images show the wave embedded in a large area of dry air in the Saharan air layer with few severe thunderstorms. Otherwise, conditions were favorable for development, with wind shear speeds of 5-15 knots and sea surface temperatures near a record high of 29 degrees Celsius (84°F).

Disturbance forecast

A strong ridge associated with the Azores-Bermuda High will direct the disturbance to the west-northwest through Friday, when it will approach the southeastern Bahamas and Hispaniola. The atmosphere is expected to be steadily moist and with mostly moderate wind shear and sea surface temperatures near record levels, this disturbance provides good model support for developments on Friday or Saturday. A stronger, earlier-developing system is more likely to move north through the Bahamas and pose a threat to the Carolinas early next week. This is the favored solution for European model Tuesday 0Z and 6Z operations. A weaker, slower-developing system is likely to move south, potentially affecting the Dominican Republic, Haiti, eastern Cuba and Florida before entering the Gulf of Mexico early next week. Disruptions in circulation through the mountainous Greater Antilles will slow development. This is the preferred solution for the 6Z Tuesday run of the GFS model and the 0Z Tuesday run of the UKMET model. None of the models show the disturbance becoming a powerful hurricane within the next seven days.

By Saturday, a trough of low pressure approaching the U.S. East Coast will disrupt the high-pressure ridge guiding the disturbance, pulling it northwestward. If the disturbance is far enough away, this trough will be able to pull the disturbance into the Carolinas early next week, or could cause the system to return to the ocean without hitting land.

At 8 a.m. ET Tuesday, the National Hurricane Center's Tropical Weather Outlook gave the two-day and seven-day chances of hurricane development at 0% and 60%, respectively. The first hurricane search mission is scheduled for Thursday afternoon. The next name on the list of Atlantic storms is Debbie. Based on data from 1991-2020, the average date of a “D” storm, the fourth naming system for the Atlantic season, is August 15.

Tropical cyclones remain on hold in northern hemisphere

Aside from the massive damage caused by Hurricane Beryl, the world's only Category 5 storm in 2024, tropical cyclones north of the equator haven't done much damage this year. According to statistics from Colorado State University, as of July 30, the cumulative cyclone energy in the Northern Hemisphere was only 64.4 units. This is slightly less than 50% of the long-term average (1991-2020) for that date. The Northern Hemisphere also saw only about half the average number of named storms (9 vs. 18.2); less than half the average number of named storm days (30.0 vs. 72.2); and only 3 hurricanes vs. the average of 8.7.

According to these data as of July 30, without Beryl in the North Atlantic, activity in each of the four Northern Hemisphere basins would be well below their average:

North Atlantic: 36.1 (average 9.4)

Northeast Pacific (East of the International Date Line): 1.6 (average 41.5)

Northeast Pacific (West of the International Date Line): 25.0 (average 72)

North India: 1.7 (average 9.5)

There is no obvious single factor behind the hemisphere's quiescence. In the Atlantic, sea surface temperatures in major development areas are now warmer than the typical early October peak, and the lull we see in mid- and late July is largely due to the continued, widespread intrusion of dry, dusty air – the Saharan air layer . This is typical for July. In the Northeast Pacific, La Niña seasons, such as this year, tend to be less active than normal. Meanwhile, in the northwest Pacific, the number of tropical cyclones tends to decrease in the summer following strong El Niño events, such as the one occurring in 2023-24.

We will post daily updates in this article.

We help millions of people understand climate change and what to do about it. Help us reach more people like you.