Author: E. Calvin Besner

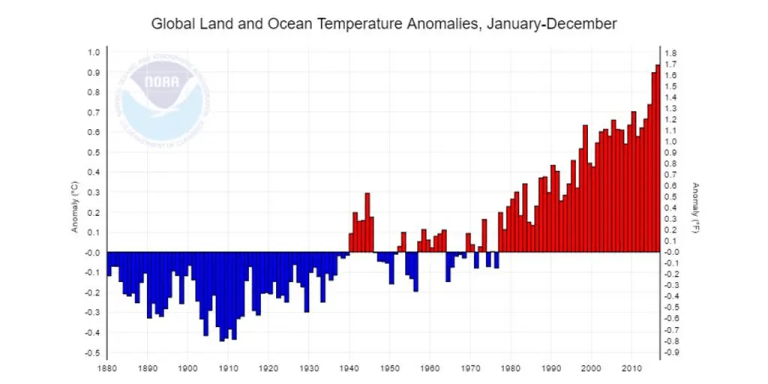

By now, nearly everyone who follows climate change news and commentary has seen graphs of global warming over the past century or more. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) produced this report in 2017, covering the years 1880 to 2016.

Since it first appeared, it has been one of the most commonly used, whether in academic journals, government websites, news media, blogs, or social media. Recent data is often communicated in a similar way – and it's not hard to see why.

Here, the solid bars, one for each year, describe changes in global mean temperature (described as anomalies, i.e. deviations from 20th-century average), the psychological impact is predictable: fear.

how? The early bar charts were below average and a comfortable blue; subsequent bar charts were above average and a shocking red. If all the bars were the same color, the psychological impact of different colors would disappear.

But color selection isn't all. They're just the most obvious. The alternative is less obvious, and readers unfamiliar with how to interpret graphical representations (or misrepresentations) of data may not notice it.

Unfortunately, the longest blue bar reaches almost to the bottom of the chart, and the longest red bar reaches almost to the top. Why? Because the chosen vertical axis (note that word – it's a clear choice) only covers -0.5°C to +1.0°C (-0.9°F to +1.8°F). Total 1.5°C (2.7°F).

On one hand, this makes sense. Plug the raw numbers into common spreadsheet software, let it produce a bar chart, and you'll get it, or something very close to it. So why not? After all, it houses all numbers, from the lowest to the highest. What more can we ask?

On the other hand, if your purpose is to help people think rationally about global temperature changes, that's completely untenable.

Why? Because to the uninitiated, it makes a temperature change of less than 1.5°C (2.7°F) look much more severe than it actually is. After all, most people will barely notice if the temperature of a room increases or decreases that much. But on this vertical scale, the longest red bar almost reaches the top, as if to say, “We're about to hit the maximum!” Indeed, the longest blue bar also almost reaches the bottom, which could be interpreted as: “Wow! We're about to hit the max!” Almost froze! (On average, cold snaps kill 10 to 20 times more people per day than heat waves, which is really comforting – but I digress.)

But remember, blue is a comforting color; red often means “danger!” After all, that’s why UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called the first volume of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sixth assessment report “Code Red represents humanity,” not “Code Blue” (granted, in hospitals, “Code Blue” means a patient is in critical condition, but that's not common lingo).

Since most people read from left to right, the chart subtly conveys the message that whatever risks these cold temperatures may bring, we are leaving them far behind. Don't worry about them now. What we need to worry about are those relentlessly rising temperatures.

Back in the early 1990s, when I was the managing editor of this book human conditionIts editor-in-chief, the late economist and statistician Julian L. Simon, was famous for his aversion to misleading statistical charts, insisting that 58 authors, including eight Nobel Prize winners, All information graphics provided by recipients use realistic, objective scales.

For example, a graph of information expressed as a percentage should have a vertical scale of 100 points, otherwise the results can be very deceptive. After all, if the vertical scale only increased from 80% to 90%, the 86% data point might appear to be twice as numerous as 83%, when in fact it is only 3.6% higher.

Another example: Information graphs that don't depict percentages should have a zero baseline. Alternatively, if they depict both negative and positive data, the vertical axis should extend equally below and above zero, so the relative sizes will be quick and easy to understand. Alternatively, if they describe data that are so different that low numbers disappear, then they should be plotted on an exponential scale—and that fact should be communicated prominently—or with clearly marked discontinuities along the vertical axis sex.

There are other examples, but you get the idea. One of the basic principles is that the vertical axis should cover what really matters.

This is the bigger problem with NOAA's famous chart. As we saw above, it makes small changes in temperature appear larger and more significant.

A more appropriate and less misleading way to plot the same temperature profile is to use the vertical range of typical weather that people generally experience. This is a scale they can understand.

In the United States, the diurnal (high daytime to low nighttime) temperature range in humid areas is typically about 5.6°C (10° F) But in arid to semi-arid areas, the temperature is about 22.2°C to 27.8°C (40°F to 50°F). In other words, people have become accustomed to these temperature ranges.

It seems reasonable, then, to describe the global temperature anomaly data on a vertical scale, such as midway between the low and high ranges, i.e. 16.7°C (30°F). And, to avoid psychological scare tactics altogether, we're going to ditch the color scheme and use neutral colors.

How would NOAA's data from 1880 to 2016 be described? like this:

Keep in mind that this describes the exact same data as the NOAA chart. Does it look scary? No, but this is a more honest, objective, non-manipulative account of the data. So, now you're ready to not be manipulated and inspire your friends and neighbors.

Someone who defends this dire way of describing the data might respond, “But the fact is that this seemingly small change in average global temperatures, if continued on a large scale, will cause changes in weather, sea levels, crop production, and other measures.” Devastating changes—changes that will impoverish humanity and possibly lead to its extinction—are just what we need.

But the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change firmly disagrees. 2018 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.8°C The conclusion is that if we do nothing to slow down the warming caused by greenhouse gases, warming will reduce gross world product (GWP) in 2100 by 2.6% compared to what it would have been otherwise.

What would happen otherwise? The Center for Global Development says economic growth for the rest of the century is most likely to be around 3% per year. After taking into account demographic changes, the per capita global warming potential will be 8.8 times higher than in 2018.

Would anyone consider this a catastrophic outcome when poverty poses far greater threats to human health and life than anything related to climate and weather?

If you spend any amount of time on social media sites, where people often post words or images intended to express opinions on controversial issues, you're bound to see “fact checks” stating that posts convey “false or misleading statements.” sexual information” because it was “lack of context.” (This judgment is often subjective and driven by the ideology of the “fact-checker,” but we can ignore that for now). What you know now is that official government agencies are probably some of the worst offenders when it comes to the “missing context” of climate change, not only on social media but also on agency websites – their products like NOAA Chart evaluations) are sourced from these sites here, and they appear regularly in scientific journals and mainstream media.

A Google image search on July 11, 2024 found NOAA charting on about 100 websites. Where are those “fact checkers” when we need them?

Dr. E. Calvin Beisner is Cornish Creation Stewardship Alliance, a Christian think tank dedicated to environmental stewardship and economic development for the poor. He also co-edited with Dr. David R. Legates Climate and energy: the case for realisman Amazon bestseller.

related