Taken from Bank of England report

Terry Ettam

With all due respect, Ozzy Osbourne is a man who lives the life of a rock star; who drinks enough booze to float an aircraft carrier; who takes enough drugs to shock a small country; who survives Having done all this, started a family, lived to be 76/and counting, and is worth $200 million…this is not a crazy person. This is genius. Well played, sir.

On the other hand, the story of natural gas markets and producers can rightfully claim this title.

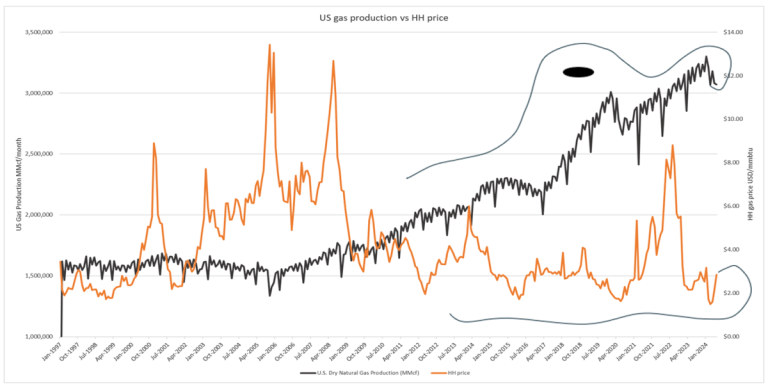

Don't take my word for it. Take a look at this chart, which plots U.S. natural gas production (black line) and Henry Center prices (orange) over the past quarter-century or so:

You may be wondering in what industry would manufacturers ramp up production so quickly while simultaneously driving prices down the toilet. You wouldn't be crazy to ask this question. During the arrow above, the industry gave a whole new meaning to the term “value destruction.” Surprisingly, investors didn’t care about the strategy at all.

Taken individually these two arrows do make the market look crazier than 8th It's pretty dire at Main Street (Calgary's upcoming East Hastings agency) at 7 p.m., but, to be fair to the troubled participants, there's some context to explain.

First, the gradual increase in production starting around 2006 was the result of the high prices of 2002-2006, which stimulated development and led to the release of abundant shale gas resources in the United States. High prices pay for shale exploration and experimentation, laying the foundation for future growth.

One of the biggest reasons for these crazy trajectories is the industry's continued advancement in extracting natural gas from hard formations. (While there are many ways to improve drilling and completions, these advances should not be confused with the simple act of drilling longer horizontal wells, which is often viewed as an efficiency gain—capital efficiency gains, no doubt, but Unlike improved fracturing – longer laterals just erode the reservoir faster and one day in a year or two we'll look back and be like, oh yeah, maybe that was important…).

These technology/fracking improvements drove the first wave of growth, but do not fully explain the steepest part of the curve. Pay special attention to the pink shaded box, which corresponds approximately to April 2017 to April 2021. USD/mmbtu fell to $2.00. People like Warren Buffett really don't like this antics.

Sure, these trajectories do seem like the product of madness, but like almost everything that happens in history, we have to go back to the context of the times. During this period, a significant amount of new gas pipeline infrastructure was commissioned, projects that had been initiated a few years earlier during 2014-15, when it became clear that there was a market for all the new gas. Pipeline and gas plant builders require volume commitments from producers to build the infrastructure, so once that's done, producers do what they're obligated to do – fill the pipeline.

From a macro perspective, this worked – the pipeline did fill up, but on the other hand, enthusiasm led to some pretty spectacular bankruptcies (hello, Chesapeake). Producers burned through huge amounts of cash and flooded markets that couldn't bear the output.

From an energy perspective, the importance of this (over)development cannot be overstated. In 2006, the United States produced about 50 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d); 18 years later, its production exceeded 100 bcf/d. At the beginning of this century, about 20 years ago, the United States was looking to build LNG import Terminal; 20 years later, the United States becomes the world’s largest natural gas producer exporter. Now this is really crazy.

Today, in mid-2024, the future is filled with uncertainty. We know something: The United States (and Canada) both have the ability to produce more natural gas. We know that demand will increase by at least 30% over the next five years due to new LNG export terminals and data center/AI requirements.

What we don't know is how easy it will be to build any new infrastructure to enable new volumes to get to where they need to be. Of course, in Canada we're used to this, it's a problem through and through; the completion of the Coastal Gas Link is a miracle, and it's hard to imagine any entity having the guts to try any new greenfield interprovincial infrastructure, which is federal Regulatory, which means the governing coalition will laugh at you even from Parliament Hill. Your briefcase appears.

The United States is not far behind. The only major interstate natural gas pipeline to come online in the past few years is the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which was delayed for years due to numerous activist attacks and was completed for twice the initial cost estimate (MVP first proposed it in 2014, It is scheduled to be put into operation in 2018; ventilation will eventually begin in 2024). A more realistic take on the current U.S. natural gas interstate pipeline system: July 2020’s Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a massive and critical new pipeline to carry excess Appalachian natural gas to a thirsty America East Coast, the pipeline has been planned for six years and is on hold despite a 7-2 vote by the U.S. Supreme Court (from the project cancellation press release: “A series of legal challenges to the project’s federal and state permits have led to Significant increases in costs and delays to $8 billion… This new information and litigation risk, along with other ongoing execution risks, make the project too uncertain to justify the investment of additional shareholder capital.

Underscoring how difficult it would be to actually build a new pipeline, Dominion Energy, one of Atlantic Coast's partners, took a $2.8 billion deduction from earnings when it canceled the project. Think about it. One public company chose to take a $2.8 billion loss rather than try to build a new, approved pipeline.

Of course, things are more complicated than this oversimplification. Texas, for example, has no problem building pipelines within the state. Texas produces large amounts of natural gas, and many LNG terminals are or will be located there. Therefore, this may be a way for natural gas production to grow. Likewise, AI data center owners are discovering that they can build data centers next to natural gas fields, thereby bypassing a host of headaches—no interstate gas pipeline requirements, avoiding grid transmission/distribution costs, Complete construction in months instead of years. Therefore, there is another clear path between producers and consumers that may lead to increased production and consumption.

But things won't go that smoothly. Over time, the big fields will turn into smaller ones, and new developments will likely be in other states. The inability to build natural gas infrastructure will plague the economy in some way. Associated gas may or may not continue to flood the market, and its availability is as important as oil prices and other factors.

And then on top of this complex business, there's the political dimension. One presidential candidate hates hydrocarbons and has supported a ban on fracking in the past. Another candidate has vowed to cut energy prices in half, a promise that would be unbelievable at the best of times and would cause brains to explode if he included natural gas prices. He wants to chop Those ones half? See: Picture above…not sure this is a well thought out proposal, not on the gas side anyway.

Add all of this together and it's a unique market, and it's very difficult. A wise colleague provided his own version of the chart above, a Rorschach analysis that may be more relevant to anyone in the natural gas business today. The beast is obvious if you play in this sandbox:

any. Something will pop up that throws the gas market into more of a convulsion, and within a year, gas will hit 50 cents or $12, or maybe both in a day. Please don't look behind the curtain. We are not good.

What the world desperately needs—energy transparency. There were also a few laughs. Learn about the end of fossil fuel madness,Can be found in Amazon Canada, Indigo.caor amazon.com.

Relevant