Thanks to new research published this month, it may be possible to more accurately predict periods of increased hurricane activity weeks in advance.

The study, led by the National Science Foundation's National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR), shows that twice as many hurricanes formed two days after the passage of massive atmospheric waves known as Kelvin waves. The discovery could allow forecasters and emergency managers to predict hurricane swarms days to weeks in advance.

The research team used innovative computer modeling methods to tease out the effects of Kelvin waves, large-scale atmospheric waves that can extend more than 1,000 miles in the atmosphere and shape global weather patterns.

“For example, if weather forecasters can detect Kelvin waves over the Pacific Ocean, they can predict that hurricanes forming over the Atlantic Ocean will intensify a few days after the Kelvin waves occur,” said Rosimar Rios-Berrios, NSF NCAR scientist in the paper. main author. “This will help them communicate with emergency managers and local governments, who can prepare for the possibility of active hurricanes and warn the public. This research has the potential to save many lives.

The study was published in monthly weather review.

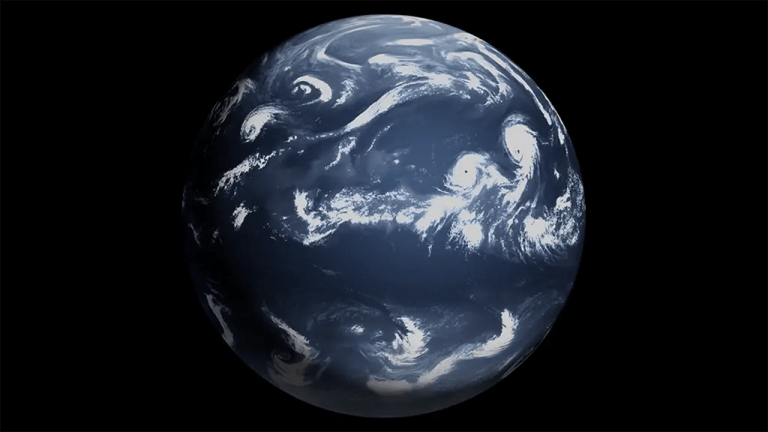

water planet

For decades, scientists have noticed hurricanes forming in clusters, followed by weeks with little to no hurricane activity. Several studies have suggested that Kelvin waves may be responsible for hurricane surges, but scientists have been unable to isolate other potential factors and prove that Kelvin waves are responsible. To overcome this problem, Rios-Berrios and her colleagues used a novel combination of computer modeling tools to confirm that Kelvin waves indeed contribute to hurricane formation.

The research team used a simulation called aquaplanet, which runs on the NSF NCAR Cross-scale prediction model (MPAS)a next-generation computer model that simultaneously captures fine-scale weather phenomena and global-scale atmospheric patterns. Aquaplanet is a configuration that simulates a hypothetical world that behaves like Earth, but without landmasses or seasons. The simplified world serves as a laboratory, making it easier to isolate the impact of Irvine waves on hurricane formation.

The scientists conducted the simulations on the Cheyenne supercomputer at NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center.

To study the connection between Kelvin waves and hurricanes, the team measured the number of days between hurricane formation and the crest of the Kelvin wave. Measurements showed a significant spike two days later, with hurricane development twice as likely. Because the aquaplanet simulation captures the physics of hurricane formation, the results go beyond correlations and show that Kelvin waves are actually influencing hurricane formation.

New research also highlights recent research Rios-Berrios co-authored an article with NSF NCAR postdoc Quinton Lawton on the need to improve the ability of weather forecast models to simulate Kelvin waves.

“I started this research on Kelvin waves in 2017. It was a large project that took several years from an idea to scientific results, and really highlights why this type of research is so valuable,” Rios-Bey said. Rios said. “There are still many gaps in scientific knowledge about how hurricanes form, and studies like this can help us narrow down where scientists should focus to better understand these powerful storms.”

paper:

title: Regulation of convection-coupled Kelvin waves on tropical cyclone occurrence

author: Rosima Rios-Berrios, Brian Tang, Christopher Davis and Jonathan Martinez

Magazine: monthly weather review

Relevant