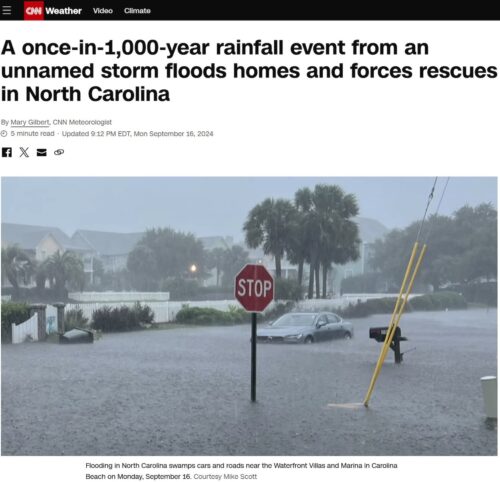

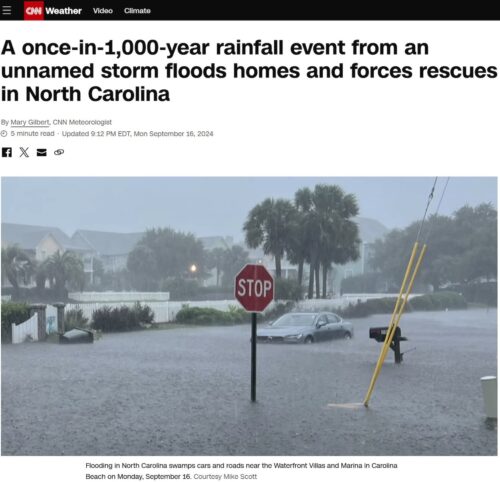

When the media claims that we are experiencing a “once in 500 year” or “once in 1,000 year” weather event, they are missing a fundamental point about how the data works. As a geoscientist, this is my perspective and I am acutely aware of it. . [emphasis, links added]

In geology, we study Earth's long history through rock formations, sedimentary layers, and the fossil record, which help us track major climate trends and changes throughout Earth's history.

We can interpret signs of past floods, droughts and temperature changes, but there's a key limitation: Geological indicators cannot capture day-to-day extreme weather.

You may find evidence of long-term sediment accumulation or erosion caused by ongoing climate conditions.

For example, we can see signs of long droughts or heavy rainfall over thousands of years, but you're not going to find fossils or rock formations that tell you, “Oh, in this particular place, 10 inches of rain fell in 24 hours. ” One day 2000 years ago. “That's not how agencies work.

Proxies give us long-term general trends rather than the hyper-detailed weather data needed to make statements about rare events such as the “Millennium Storm.”

The truth is, these assertions are based on shaky statistics, and given how little data we actually have, we can't really determine the frequency of these events.

The Statistical Absurdity of Rare Event Claims

When we talk about such a rare event, such as a “once-in-a-millennium” flood, we are referring to statistical probabilities based on the observed distribution of events over time.

The tails of any statistical distribution, especially one that measures the frequency of rare extreme events, are always the hardest to fill.

So when the MSM declares a particular weather event to be in the “500-year” or “1,000-year” category, it's often based on incomplete data, assumptions and models that are far from deterministic.

In my last article , I highlighted the problems of relying on a limited data set when making sweeping claims about extreme weather events.

I pointed out that the high-side tail takes the longest to fill because, by definition, extreme cases are rare. This means that the further out we spread, the more speculative the claims about the frequency of such events become

The high side tail takes the longest to fill

Here's an analogy that might help: Imagine you're filling a jar with marbles, but some marbles are much rarer than others. Assume that most of the marbles are white, but there are some rare blue marbles mixed in.

You've been scooping marbles into jars for years, but so far you've only found a few blue marbles. One might be tempted to say that finding blue marbles is extremely rare, perhaps a “one in a thousand” event. But if you only grabbed 50 times, that conclusion is premature at best.

The same principle applies to extreme weather. We're dealing with a relatively short data collection period, so we're just starting to fill in the rare “blue marbles” of extreme weather events.

Yet the media and even some scientists act as if we have mapped the entire distribution.

Insufficient historical data

The fundamental problem is We simply do not have immediate data over a long enough time period to make strong assertions about the frequency of such rare events.

Weather records in most areas only go back about 150 years, High-quality, granular data has only recently become available. This is a far cry from the 500 or 1,000 years it would take to reliably estimate the occurrence of these so-called extreme events.

Imagine trying to estimate the frequency of rare weather events from a data set that covers less than a third of the time required for the “500-year” claim.

The statistical uncertainties become enormous, and any claim about a “thousand-year event” becomes almost meaningless in this context. You'd need more observations of such rare events to confidently make even modest claims.

As I detailed in my article titled “Surrounding the Past…,” historical weather and climate data are often manipulated to fit a particular narrative. We see the same trend in coverage of extreme weather events.

Without a full understanding of statistical limitations, narratives are often oversimplified, eliminating uncertainty to provide dramatic headlines.

Irrational Fear is written by climatologist Dr. Matthew Wielicki and is supported by readers. If you value what you read here, please consider subscribing and supporting the work.

Read A Break from Irrational Fear