From NASA's Earth Observatory:

In March 2024, ozone concentrations over the Arctic reached a record monthly average. All more.

A team of scientists from NASA and the University of Leeds reported their findings in a paper published in September 2024 Geophysical Research Letters. “Given that Arctic ozone has been absent since the 1970s, the record high in March 2024 should be viewed as a positive harbinger of future Arctic ozone,” the authors wrote.

Between December 2023 and March 2024, a series of planet-scale waves propagated upward through the atmosphere, slowing down the stratospheric jet stream that circulates around the North Pole. When this happens, air from mid-latitudes converges toward the poles, sending ozone into the Arctic stratosphere. In addition to the influx of ozone, typical ozone depletion from substances like chlorine is minimal, said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and lead author of the study. “This is a very dynamic, active winter in the northern hemisphere,” he said.

More stratospheric ozone is good for life on Earth. The stratospheric ozone layer acts as a natural sunscreen, absorbing harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. The authors calculated that from April to July 2024, the UV index decreased by 6% to 7% in the Arctic and by 2% to 6% in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Less UV radiation means less damage to plant DNA and a lower risk of cataracts, skin cancer and suppressed immune systems in humans and animals.

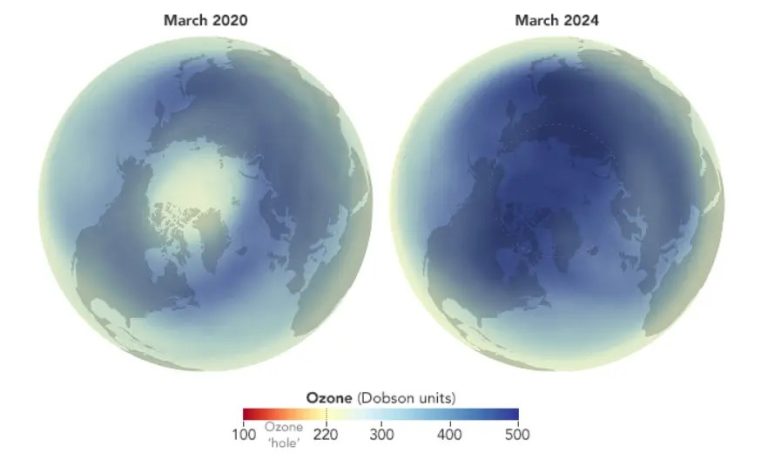

Activity in March 2024 was in stark contrast to March 2020, when stratospheric ozone concentrations fell to very low levels. In the absence of interference from upper atmospheric wave events, stable circumpolar winds prevent ozone from other latitudes from replenishing the Arctic stratosphere. A stable polar vortex also creates colder-than-average conditions that favor ozone-depleting reactions.

The map above shows ozone concentrations over the Arctic in March 2020 (left) and March 2024 (right), illustrating the dramatic changes that can exist there. Monthly averages are calculated by the NASA Ozone Observation Team based on data obtained by the OMPS (Ozone Mapping Analysis Suite) aboard the NASA-NOAA Suomi-NPP satellite.

Newman said that unlike Antarctica, where an ozone hole forms every year, ozone concentrations over the Arctic vary widely and are affected by “year-to-year changes” in tropospheric and stratospheric weather.

1979 – 2024

Strong wave events from late December 2023 to early March 2024 resulted in increased ozone concentrations, as shown in the figure above. As usual, ozone levels peaked in March and remained well above average thereafter. Monthly average ozone concentrations also set new records in May, June, July and August. “This has truly been an extraordinary northern summer,” Newman said.

As for what causes the unusual stratospheric weather, the authors looked at a variety of factors but found no clear answer. For example, the effects of climate change are difficult to quantify. “There may be a climate factor here, but it's not obvious,” Newman said. For larger atmospheric patterns such as El Niño and the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation: “It's possible, but the contribution is relatively small.”

In addition to stratospheric weather, the main determinant of ozone levels in the Arctic, the authors suggest that long-term trends could bring ozone concentrations to record highs. Ozone levels have been slowly recovering since the 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out the production of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons. The high level in March 2024 was therefore within the authors' expectations: the Goddard chemical climate model GEOSCCM shows a one in eight chance of a record high by 2025, with more records expected in the future. However, they note that because CFCs persist in the atmosphere for decades, Arctic mean ozone is not expected to return to 1980 levels until around 2045.

Higher greenhouse gas concentrations in the stratosphere also accelerate ozone recovery. “This record is probably the result of a decrease in ozone-depleting substances and an increase in greenhouse gases. Otherwise, it's only It was a high-level year, but not a record year,” Newman said. “I call this year a harbinger of things to come.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using data provided by NASA's Ozone Observatory. Story by Lindsay Dullman.

Relevant