As I see the devastation caused by Hurricane Helene, with homes flooded, lives upended and entire communities thrown into chaos, my heart goes out to those facing unimaginable loss. This is a stark reminder of the toll these natural disasters take on humanity. [emphasis, links added]

But when we face these tragedies, we must also take a critical look at how we respond to them. Have we truly addressed the root causes, or are we stuck in a cycle of rebuilding in the same vulnerable areas, only to see them destroyed again?

The recent hurricane Helen has reignited the debate about the relationship between extreme weather and climate change.

Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Dean Criswell's speech focused on warming waters and rising storm intensity, reflecting a narrative that links these disasters to global climate trends.

However, existing data on hurricane frequency and historical comparisons with the 1916 Appalachian storm complicate the picture and raise questions about how we should respond to such disasters.

Analysis of Administrator Criswell's Statement

Chief Criswell said in a recent interview with CBS that the rapid intensification of recent hurricanes, including Helen, was largely due to warming waters in the Gulf of Mexico. She believes these conditions are fueling more frequent, more powerful storms.

Administrator Criswell: Well, I think what we're seeing, Robert, is that, you know, it took a while for this storm to develop, but once it did, it developed and intensified very quickly and that's because Mexico The warm waters of the Bay and as a result, it is creating more storms reaching this major category level than we have seen in the past. It also causes larger storm surges along coastal areas. As it moves north, it produces more rainfall. So in the past, when we saw damage from hurricanes, it was mostly wind damage, and some water damage, but now we're seeing a lot more water damage, and I think that's a result of warmer waters, that's a result of climate change.

This view has strong support from policymakers and some scientists, arguing that human-driven climate change is the root cause of these escalating natural disasters.

However, historical and meteorological data provide a more complex picture.

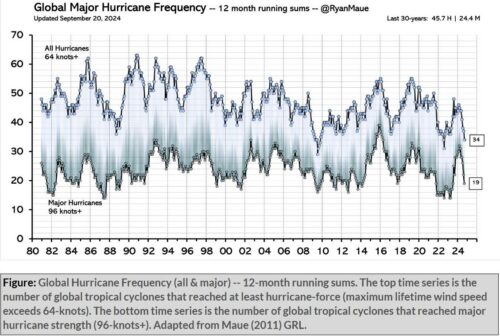

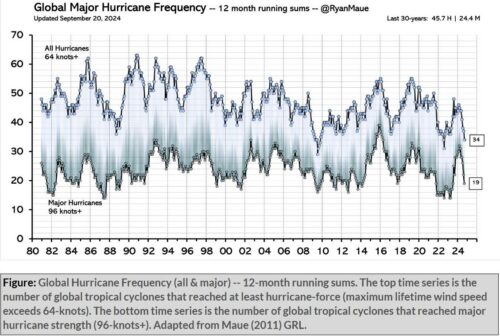

Despite increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, the frequency of large hurricanes (≥96 knots) fluctuates over time, following cyclical rather than linear trends.

Meteorologist Dr. Ryan Maue's data on a 12-month running total of global hurricane frequency reveals periods of increases and decreases over the past few decades, casting doubt on the idea that climate change is the sole or even the main driver behind these storms.

While the number of hurricanes is often used in discussions about the effects of climate change, the frequency of storms does not necessarily indicate whether storms are becoming more intense.

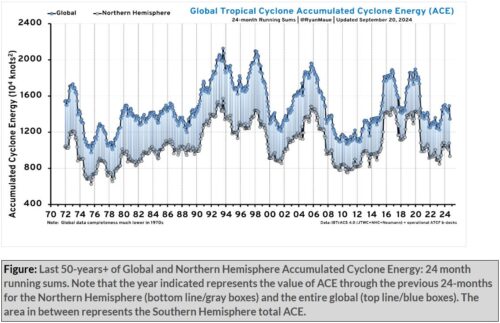

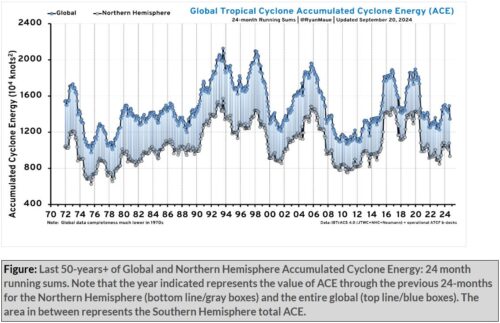

To assess whether hurricanes are getting stronger, a more reliable metric is cumulative cyclone energy (ACE), which takes into account the duration and intensity of tropical storms and hurricanes.

The graphs provided of global and Northern Hemisphere ACE data over the past 50 years show no significant upward trend in cyclone energy.

Actually, The data showed periods of fluctuation in storm intensity, but no sustained increases. This means that while storms like Hurricane Helene can be devastating, There is no clear evidence that climate change is “exacerbating” hurricane systems as a whole.

ACE remains an important tool in understanding storm energy, showing that changes in storm energy, rather than dramatic intensifications, are part of natural systems.

Hurricane Helen compared to the 1916 storm

To provide historical context, it is useful to compare Hurricane Helene to the 1916 storm that devastated Appalachian towns.

The July 1916 flooding in Asheville, North Carolina, was caused by two consecutive tropical systems that brought unprecedented rainfall to the area.

This resulted in the worst flooding in Western North Carolina's history. Flood levels on the French Broad River in Asheville reached a staggering 21 feet, rising rapidly as the ground saturated and rivers and streams flooded.

This flood inundated entire areas of Asheville [pictured above, below]destroying homes, businesses, and railroads and leaving a large amount of debris.

Several Appalachian towns suffered unprecedented damage, with many areas submerged under several feet of water.

The 1916 storm caused rivers such as the Swannanoa River to swell and overtop their banks, affecting communities that lacked flood protection infrastructure.

The region is struggling to recover from the disaster, and the economic damage and loss of life have been enormous.

At the time of the 1916 event, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were about 120 ppm lower than today.

By comparison, Hurricane Helene recently caused flooding in Asheville. While exact numbers may not yet be finalized, NOAA shows Asheville's French Broad River peaked at 24.67 feet following Hurricane Helene.

This level exceeds the 1916 flood level, which reached a record high of 23.1 feet. This new peak shows the severity of the storm and the risk of severe flooding in the area.

The 1916 event shows that extreme weather events of similar magnitude were occurring long before human-driven climate change became a prominent factor.

Hurricanes are a natural part of the Earth's climate system, and their occurrence is influenced by a variety of factors, including natural climate variability and ocean patterns.

Comparing the two storms highlights an important point: While the frequency and intensity of hurricanes may fluctuate, they are not unprecedented.

The 1916 storm reminds us that catastrophic weather events have always occurred and will continue to occur regardless of human activity. This context raises questions about how we should interpret and respond to current events such as Hurricane Helen.

Irrational Fear is written by climatologist Dr. Matthew Wielicki and is supported by readers. If you value what you read here, please consider subscribing and supporting the work.

Read A Break from Irrational Fear