The 119th Congress comes at a cost.

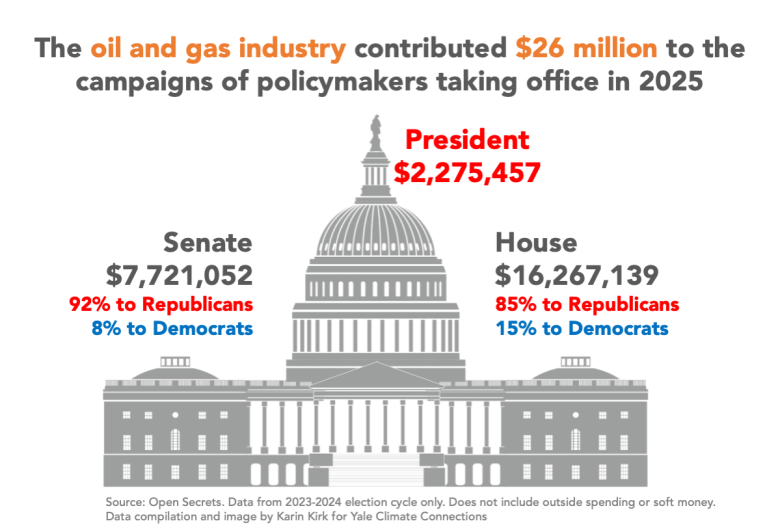

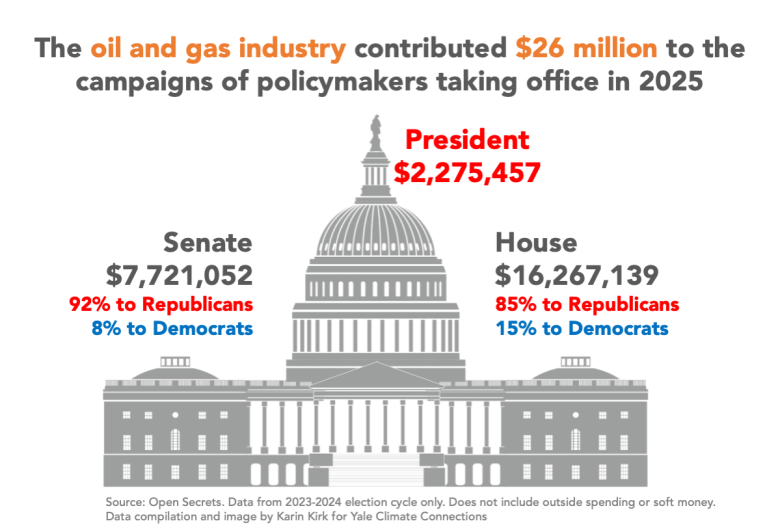

The oil and gas industry has given about $24 million in campaign contributions to members of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate who are expected to be sworn in on Jan. 3, 2025, according to a review of campaign contributions by Yale University Climate Connections. The industry provided an additional $2 million to President-elect Donald Trump's campaign, bringing the winning candidate's total spending to more than $26 million, 88% of which went to Republicans.

The fossil fuel industry exerts enormous financial power in the U.S. political system, and these contributions are just the tip of the (melting) iceberg.

Outside spending: An order of magnitude higher than candidate donations

In the 2024 presidential election, candidates' campaign committees and outside groups supporting them received more than $4 billion in various contributions. Most money in politics is not given to specific candidates. Instead, it goes to political action committees, or PACs, and party committees. This is called external spending.

According to Open Secrets, in the 2024 election cycle, the oil and gas industry injected more than $151 million into elections through this additional spending. The industry donated $67 million to candidates, including those who did not win, bringing the total amount spent by the oil and gas industry to influence the 2024 election to a staggering $219,079,058. The vast majority of that money went to Republicans, including nearly $23 million in oil and gas money donated to Donald Trump's campaign and political action committees supporting him.

These numbers include only reported contributions from individuals, political action committees and various organizations. Transactions reported to the Federal Election Commission are gathered into a user-friendly format by Open Secrets, a nonpartisan, independent research organization that tracks political donations. This data can be easily explored on the Open Secrets Oil & Gas summary page.

In 1907, the United States banned corporate funds from participating in politics.

The history of corporate money in American politics follows a complex timeline. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt signed a law banning corporations from making political contributions, a measure that was wildly popular at the time—and may be popular again today. In 1935, utility companies were banned from making political donations, further reducing corporate influence in elections. But over time, those policies were softened and eventually reversed, culminating in the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United ruling, which opened the floodgates to unlimited spending by corporations seeking political influence.

Today, money enters the political system from individuals, corporations, and special interest groups

Money from the fossil fuel industry flows into the political system in several different ways.

Individuals can contribute directly to a candidate's campaign, with direct contributions capped at $3,300 per candidate. But individuals can also donate to political action committees, state party committees and national party committees. The combined total of these different categories allows wealthy individuals to donate more than $180,000 per election, in addition to providing $3,300 each to specific candidates.

Technically, companies can't provide money directly to federal candidates, but there are many avenues through which companies can influence elections, such as super PACs or trade associations. These outside funds are used to organize, campaign and influence elections.

The Citizens United ruling allows certain types of political action committees — particularly super PACs — to solicit and accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, special interest groups and labor organizations. (See FEC's summary table of contribution limits.)

In the wake of the Citizens United movement, the fossil fuel industry's outside spending has poured into politics like never before, rising from $2 million to more than $150 million in just four presidential election cycles.

Finally, there is “black money,” which does not require disclosure of the source of the funds. Dark money allows wealthy donors and corporations to funnel money into political campaigns without them being traced. Dark money can also be spent on issue campaigns that may not be directly related to elections but contribute to the public image of the fossil fuel industry, such as ads that suggest the pollution and damage caused by burning fossil fuels is not serious. In some cases, amounts are included in the above external spending statistics, but the source of the funds is anonymous. Dark money from the fossil fuel industry plays a growing role in funding misinformation and influencing lawmakers.

Fossil fuel money in politics overwhelmingly goes to Republicans

In those quaint days of 1992, fossil fuel election spending was more equitable than it is now, with about 34% going to Democrats and 66% to Republicans. Today, Democrats still receive about the same amount of money from the oil and gas industry as they did in 1992. In the 2024 election, 88% of oil and gas money went to Republican lawmakers.

What do fossil fuel donors get for their money?

A 2019 study on the impact of oil and gas money on politics found that oil and gas companies tend to reward candidates who have voted in the best interest of their industry. In effect, industry money is used to invest in lawmakers who have a record of siding with the oil and gas industry. (Please note that several authors of this study are affiliated with the Yale Climate Change Communication Program, the publisher of this site.)

The financial power of the fossil fuel industry will not stop once the new Congress is sworn in. The industry spends more than $100 million a year lobbying politicians for legislation that would benefit the industry, such as voting against climate policies, slowing the adoption of clean energy, taking a lenient stance on pollution and imposing harsh penalties for peaceful protests.

At the same time, the industry has further used its power and influence to sow doubt about climate science, spread misinformation, and seek to influence the courts. While the damage from burning oil, natural gas and coal has become widespread, the fossil fuel industry has poured money into a variety of avenues to protect its business model.

Track your elected officials

The situation can feel overwhelming. But a good first step is to use this transparency data and make these numbers public. Through the Open Secrets website, you can easily find election information for every U.S. Senator and Representative since 1990.

This article focuses specifically on the oil and gas industry, but to gain insight into other aspects of the fossil fuel industry, you can access data from coal mining, natural gas pipelines, and electric power companies. You can also search for any federal politician in Open Secrets and learn about the industries, PACs, and individuals that donated to their campaigns.

You can find any donors on Open Secrets, and in the spirit of transparency, the repository includes the author of this article, who has made small donations to various candidates in the past few elections. The meager sums donated by ordinary citizens stand in stark contrast to the millions spent by the fossil fuel industry on electoral politics.

To learn about state and local officials' campaign finances, use the Follow the Money database.

How do politicians' voting records align with voters' wishes? You can also view the Environmental Scorecard for each member of Congress produced by the League of Conservation Voters. Yale University’s Climate Opinion Map (created by the publisher of this site) contains public opinion data on climate change, energy, and climate policy for every congressional district in the United States. Working industry interests rather than the public interest.

Dissatisfaction with big business and powerful corporations is already widespread in both parties, and an uneasy awareness of corporate power is likely to be a growing theme in 2025. place.

Only 28% of U.S. residents regularly hear about climate change in the media, but 77% want to know more. By 2025, you can show Americans more climate news.