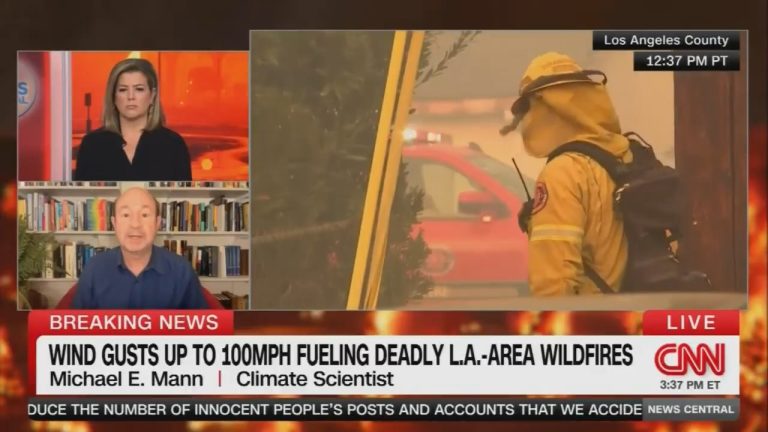

In a recent interview with CNN, Dr. Michael E. Mann attributed the devastating Pacific Palisades fires largely to climate change, saying, “15 of the 20 worst wildfires Happened in the past 15 years. [emphasis, links added]

Dramatic statement from Dr. Michael Mann…but is this the whole truth?

As California battles another inferno, it's clear that the real accelerant isn't carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but decades of poor planning and policy failures.

Exhibit A illustrates why people no longer trust “experts.” Mann, who earns a large taxpayer-funded salary at Penn State, was invited to speak to CNN on CNN despite spending much of his day smearing his political opponents on social media. People lecture on climate issues and he clearly knows nothing about it… https://t.co/pSEtgqCmiJ

— Mike Bastasch (@MikeBastasch) January 9, 2025

Before diving into the historical perspective, it is important to acknowledge and summarize the work that others have done in analyzing the factors behind the Palisades Fire.

I will not attempt to rewrite their analyses, but rather encourage you to read them directly, while providing summaries below.

My focus here will be to expand on the historical context and address California’s broader policy failures in addressing wildfire risk.

Summary of important articles about the Palisades Fire

- Analysis by Patrick T. Brown: This analysis focuses on the impact of meteorological factors, specifically Santa Ana winds, on fires. It also discusses fuel conditions and human ignition, noting that climate change plays a marginal role compared with viable solutions such as fuel management and ignition prevention.

- The Meltdown of Chris Matz: This article takes an in-depth look at the origins of fires, highlighting that all Santa Ana wind fires in Southern California (1948 to 2018) were caused by humans. It also highlights that insufficient temperature and precipitation play a smaller role than human activity and poor land management.

- Anthony Watts' point of view: This article criticizes the media’s tendency to attribute wildfires to climate change while ignoring historical wildfire data, poor land management, and the expansion of cities into fire-prone areas. It advocates practical solutions rather than alarmism.

For a detailed analysis, I encourage you to read directly to these articles. Below, I focus on expanding the historical perspective and evaluating California’s response to wildfire risk.

Wildfire historical background

Long before industrialization and the current climate change narrative, wildfires have long been a natural part of the California landscape. Historical records show that major wildfires are nothing new in the region.

For example, the 1956 Newton Fire in Malibu burned 26,000 acres, destroyed more than 100 homes, and killed one person (source).

Likewise, the Santa Monica Fire of 1938 burned parts of the Pacific Palisades (source).

These events occurred decades before climate change became a major discussion point, highlighting that Southern California's fire risk is inherent to the region's ecosystems.

Fire in a pre-industrial context

Fire has always been an integral part of California's ecosystem. For thousands of years, California's native peoples have used fire as a tool to shape ecosystems, maintain healthy landscapes and prevent catastrophic burns. Modern fire suppression policies disrupt these cycles, leading to dangerous fuel build-ups.

a study Forest Ecology and Management (Source) studied fire behavior in pre-industrial times and found Large-scale fires are common even when atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations are low.

These fires are part of a natural cycle influenced by lightning and Aboriginal land management practices.

In prehistoric times (before 1800), approximately 1.8 million hectares of land burned in California each year. We estimate that during the “extreme” decade for wildfires (1994 to 2004), California’s prehistoric annual fire area accounted for 88% of the total annual wildfire area in the entire United States. The idea that the approximately 2 million hectares of wildfires in the United States each year is extreme is certainly from a 20th or 21st century perspective.

In contrast, modern fire suppression policies disrupt these cycles, leading to dangerous fuel accumulation.

Historical fire records for Malibu and Pacific Palisade, such as those from 1938 and 1956, show: Catastrophic fires are not unique to modern times.

Urbanization in fire-prone areas

The impact of wildfires has increased significantly due to increasing urbanization in fire-prone jungle environments. The two images below illustrate the dramatic transformation of Pacific Palisades over the decades:

- Historical Image (1929): This photo shows Pacific Palisades as a sparsely populated area dominated by natural jungle vegetation. The lack of dense urban development allows wildfires to burn more freely without endangering important human structures.

- Modern Image(2024): Satellite imagery highlights widespread urbanization, with houses, roads and infrastructure now covering much of the region. This development not only increases the risk to life and property, but also complicates firefighting efforts by creating more fire points and reducing open space access to controlled burning.

The expansion of the wildland-urban interface shows that urban planning does not adequately consider fire risk. Have we learned from past fires? Judging from rising population densities in these fire-prone areas, the answer appears to be no.

The effects of Santa Ana winds

Santa Ana winds are a key driver of wildfires in Southern California. These powerful, dry winds, which can reach hurricane speeds, are a well-documented weather phenomenon caused by high-pressure systems in the Great Basin.

While some speculate that climate change may affect these winds, research shows mixed results.

For example, Guzman-Morales and Gershunov (2019) found that weakening the southwest pressure gradient driving these winds may reduce their frequency (Study).

Regardless, Santa Ana winds are as natural to Southern California as the Pacific Ocean.

Irrational Fear is written by climatologist Dr. Matthew Wielicki and is supported by readers. If you value what you read here, please consider subscribing and supporting the work.

Read A Break from Irrational Fear