The waste industry has about 20% methane emissions, the second largest greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide. Without emergency action and proper climate financing, methane emissions from the waste sector are expected to double by 2050, jeopardizing the capacity within the 1.5°C warming scheme.

Methane emissions have caused approximately one-third of global net warming since the Industrial Revolution. The average lifespan of this short-lived climate pollutant is 86 times that of CO₂’s warming potential over a decade. With low or negative cost solutions and easy-to-access technologies, human-caused methane emissions can be reduced by up to 45%, avoiding global warming by 2045. Super pollutants can also prevent premature deaths of more than 255,000 people, 775,000 asthma-related hospitalizations and 73 billion hours of labor losses each year due to extreme calories. Therefore, mitigating methane emissions is often considered to be the most effective strategy to maintain in a 1.5°C warming scheme.

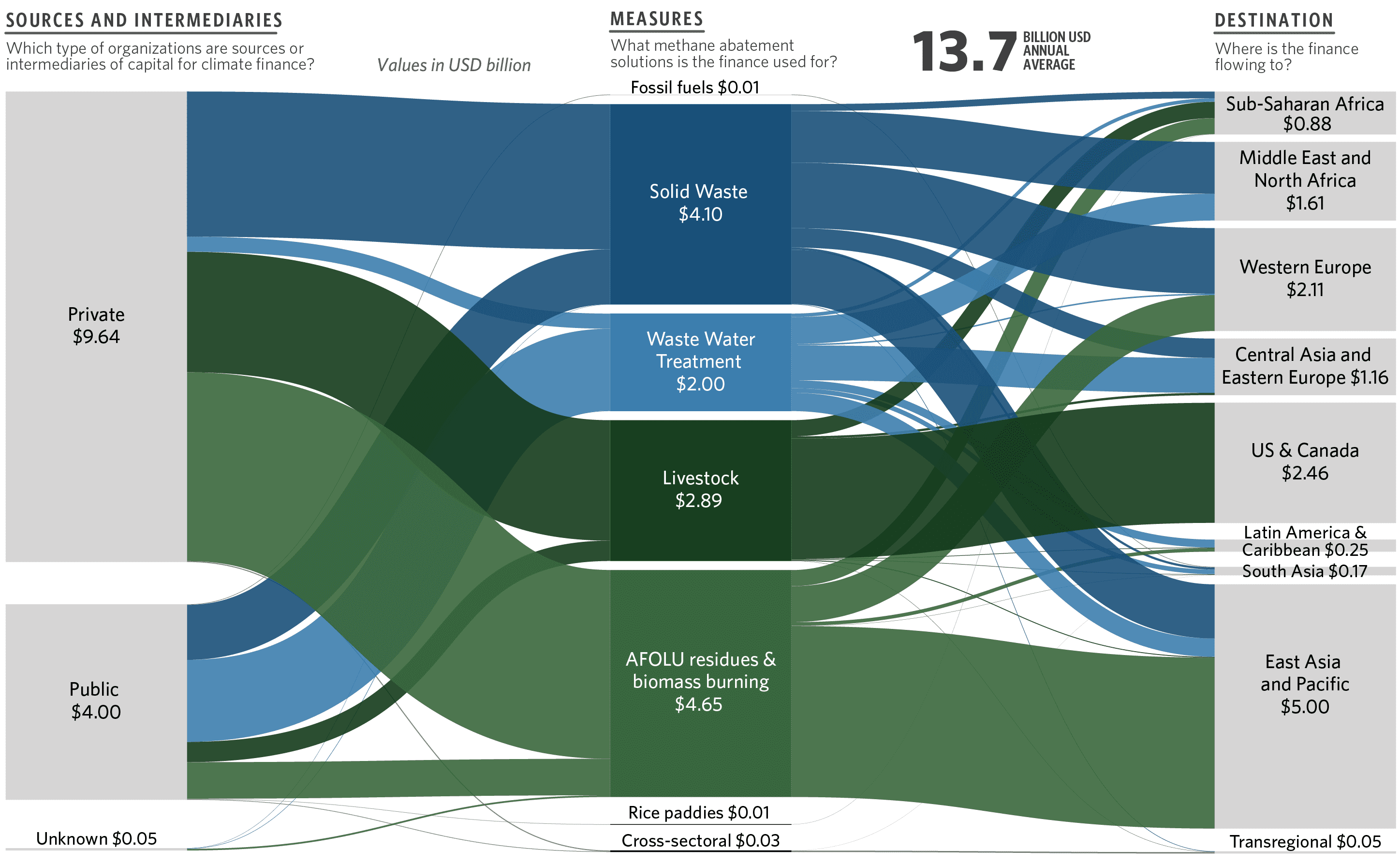

Despite methane making a significant contribution to climate change, the 2023 landscape of CPI shows that reducing methane financial flows account for only 1% of global climate financing tracked (in 2021/2022, $130 million $13.7 billion).

Figure 1: Financial landscape of methane emission reduction in 2021/2022

The waste industry is one of the fastest sources of anthropogenic methane emissions, accounting for 20% of the total, the third largest source after fossil fuels and agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU).

In the solid waste subsector, methane emissions are generated by the decomposition of organic waste in anaerobic environments such as landfills and waste bins. Despite significant contributions to climate change, methane mitigation actions in the waste industry remain seriously underfunded.

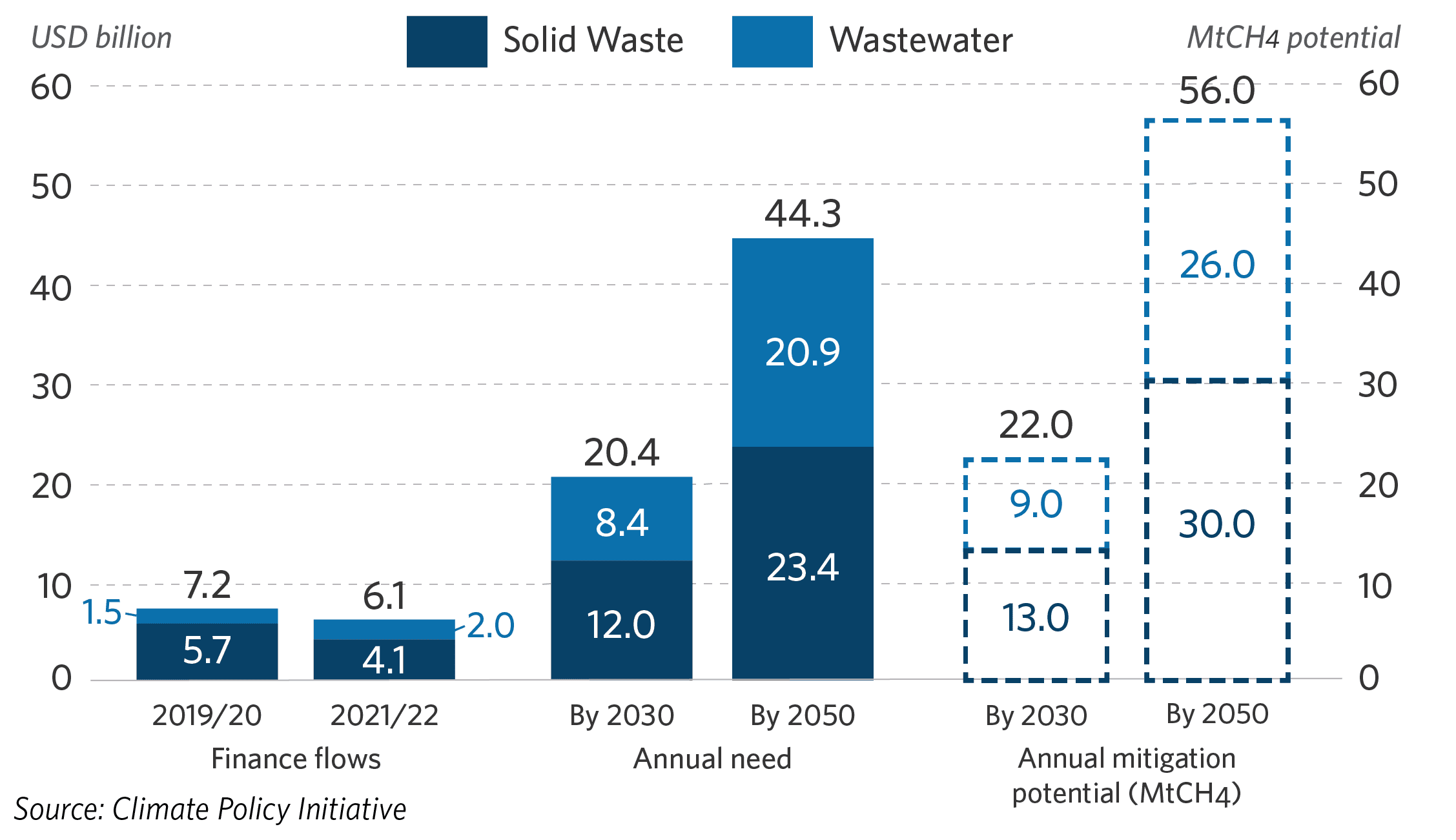

Figure 2: Waste industry reduces financing for methane compared to demand and annual mitigation potential

In 2022, only $4 billion will be used to reduce solid waste methane, well below the estimated $12 billion it needs to reach annually to meet the needs of the subsector (see Figure 2).

However, UNEP's global waste management prospects emphasize that in the usual commercial situation, the full net cost[1] The hidden costs of waste management (including pollution, poor health and climate change impacts) are expected to nearly double by 2050, from $361 billion (2020 baseline) to $640.3 billion (see UNEP's 2024 report Figure 24). Conversely, by 2050, “waste” could avoid over $370 billion of full network costs, while circular economy programs could achieve over $100 billion of net income (recycling revenues outweigh environmental and health externalities). Therefore, early resolution of waste management and methane emissions in subsectors can prove that future savings of hundreds of millions of dollars for all government pillars.

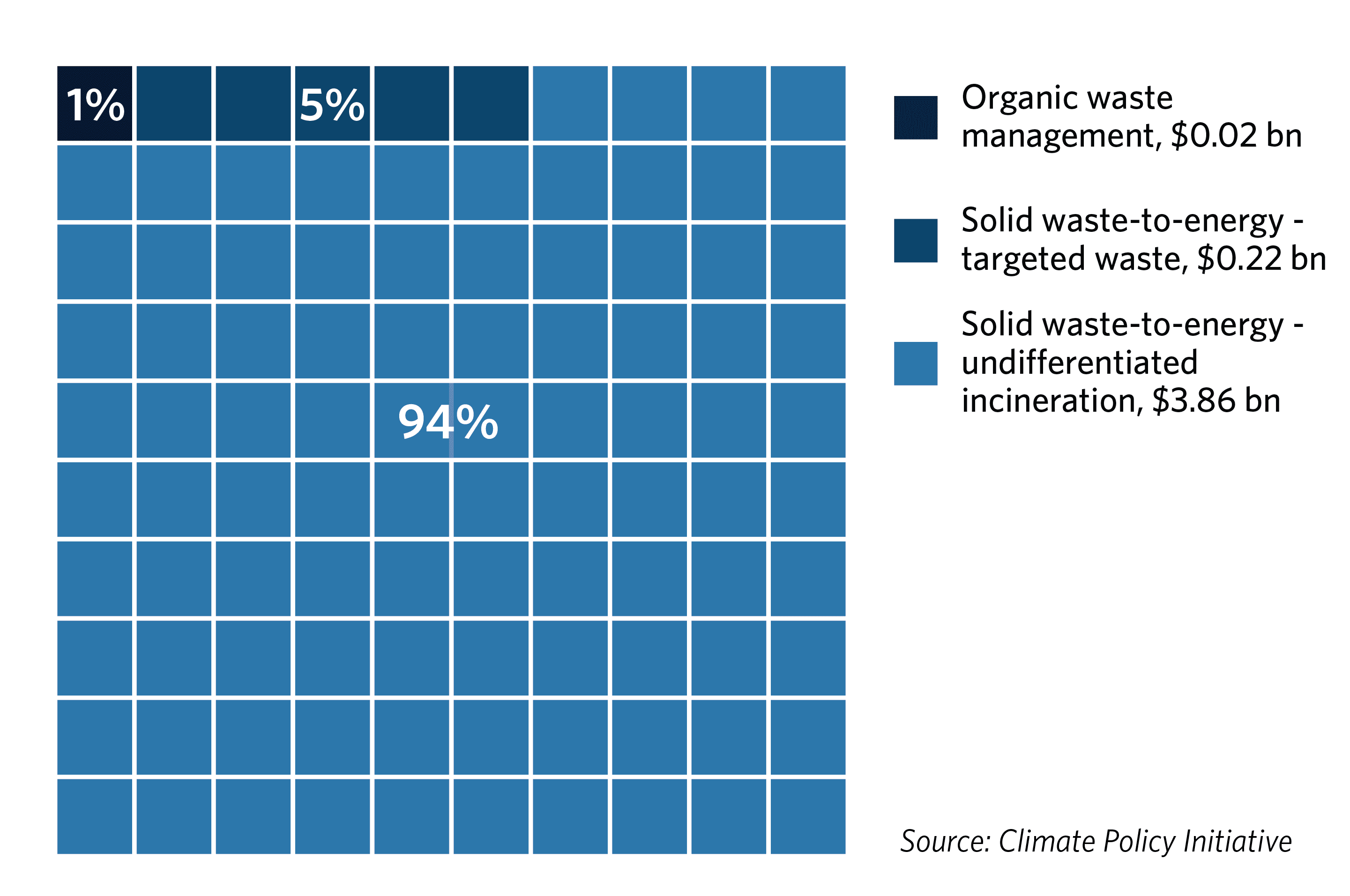

Currently, only 6% of the tracked solid waste subsector funds are used for optimally available climate strategies such as landfill gas capture and anaerobic digestion of food waste (see Figure 3). Organic waste management is a key methane reduction strategy, including a composting project, which received only $22 million in global climate financing in 2022.

Figure 3: Methane reduces financing flows in solid waste subsectors in 2021/2022

The remaining 94% use waste incineration, which generates energy, but also converts methane to Co₂, a method considered by some as an inefficient and contaminated method while posing a significant health risk to vulnerable groups.

The existing target measures can reduce methane emissions from the waste sector by 29-36 megatonnn (MT) each year to 2030, with the greatest potential by improving the treatment and treatment of solid waste. This exceeds the annual greenhouse gas (GHG) generated by electricity consumed by U.S. households, or emissions generated by more than 190 coal-fired power plants in a year.

Although 60% of waste sector reduction measures are low-cost or negative, and are expected to have various common interests, various financing barriers hinder their full potential.

Scaling methane to reduce financing challenges

Supplier Challenge (Funder)

- Availability of funds: There are few dedicated funding flows for reducing methane, especially in the waste sector. Major donors and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) tend to disprise methane in their climate strategies, resulting in insufficient financial support.

- Source of fragmented funds: Funds to reduce methane usually come from multiple fragmented sources, so it is difficult to obtain comprehensive financing for large projects. For example, a new decentralized waste management facility project may require a combination of grants, loans and private investments, each with different requirements and repayment schedules, resulting in inefficiency and delays.

- Lack of powerful MRV frameworks: Without standardized and transparent monitoring, reporting and evaluation (MRV) systems, the system tailored to reduce methane is a key challenge. An effective MRV framework involves systematic approaches to measure, report and verify greenhouse gas emissions and reductions. Without these, demonstrating the effectiveness of the project, accurately estimating actual emission levels, attracting private investment and integrating methane-centric goals into a broader climate financing strategy is a challenge.

Required-side challenge (project implementer)

- Project Sustainability: Although countries have set ambitious methane reduction targets in their nationally identified contributions (NDCs), the lack of technical expertise and financial resources has remained a significant obstacle to converting them into viable viable projects at the local level. .

- Highly relied on municipalities: More than 70% of solid waste management belongs to municipal jurisdictions that typically lack the expertise, regulatory frameworks and financial resources to implement methane reduction. In emerging markets and developing economies (EMDES), waste management can account for 20% to 50% of the total municipal budget budget, making it challenging to allocate sufficient funds for effective waste management and related methane elimination.

- Private sector participation: The private sector often sees methane reduction projects as high risk due to uncertainties in regulatory environment, market conditions and technical performance. Low ROI for such projects may limit private sector participation compared to other climate investments.

Recent advancements and emerging momentum

However, recent developments highlight the growing awareness of the role of the waste sector in mitigating methane:

- Global Methane Commitment (GMP) and COP29 Commitment: At COP29, as part of the declaration on reducing organic waste methane, nearly $500 million was announced for new grant funds to reduce methane, thus bringing the total grant funds to exceed $2 billion. However, by 2030, that is still well below the estimated $48 billion required annually.

- Low M initiatives and regional actions: Low Organic Waste Methane (Low-M) initiative aims to reduce the reduction of 1 million tonnes of methane emissions in the solid waste subsector by 2030, mobilizing up to $10 billion in investment in 40 jurisdictions. Examples of viable methane reduction strategies for low-M portfolios (targets and strategic plans) created for Santo Domingo in Lagos, Nigeria and Dominican Republic. Santo Domingo, for example, aims to reduce methane emissions by 1,600 tons/year by replacing the city’s existing La Duquesa dump with a new sanitary landfill.

- Innovative regional plans: The IDB waste initiative is so good, and the Caribbean program has introduced guaranteed and targeted funding to accelerate methane reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean Sea. Meanwhile, the World Bank's Climate Change Action Plan (CH4D) for Methane (CH4D) has provided global resources for reducing methane emissions in agriculture and waste, and has carried out successful projects in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Although these developments are promising, reducing the scaling rate of financing for methane is critical to bridge the $8 billion annual gap in reduced financing for methane required for solid waste subunits (see Figure 2). The following outlines key suggestions on how to achieve this goal.

Advice to unlock financial and expand impacts

- Methane emission reduction in the global climate finance framework: Parties to the IFCC can prioritize methane in climate finance targets, including methane-specific considerations in the new collective quantitative target (NCQG), and intervene for waste such as waste composting, garbage-filled gas capture, waste capture and anaerobic compost. Measures to establish a special fund flow. Digestion.

- Strengthen the capacity of local governments: Multilateral donors and national governments can provide technical assistance and training to municipalities to design and manage methane reduction projects and expand grants and preferential financing programs for high-impact interventions.

- Mobilize hybrid financial instruments: Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) can use hybrid finance to invest in waste-specific methane emission reduction projects through guaranteed and preferential loans and promoting public-private partnerships.

- Develop investment-friendly project pipelines: Providers of methane relief financing can help emerging markets and developing economies create investable project pipelines for waste industry plans, provide resources for feasibility studies and project design, and strengthen policies and regulations to ensure investor certainty and stability.

Scaling the critical time for methane to reduce financing

Entering 2025, there is a critical five-year window around the world to deliver and reduce methane emissions by 30% on the global methane commitment[2] By 2030. Until 2030, it is crucial to quickly bridge the financing of methane in the solid waste subsector and direct it to high-impact solutions such as organic waste management. Focusing on innovative financial instruments and community-centric solutions can also significantly promote the broader Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), good health and well-being (SDG 3) , and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), create a more sustainable, resilient and equitable future for all.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Baysa Naran, Ira Purnomo and Berliana Yusuf of CPI for their contributions to the previous draft of this blog/article, as well as Kirsty Taylor and Jana Stupperich for their review and editing.

footnote

[1] All costs include hidden costs such as pollution, poor health and climate change impacts. Net costs also account for the benefits of environmental and health effects minus externalities.

[2] Starting from 2020