A tribute to independent science and curiosity

Forrest M. Mims III is a name that people who value empirical science, institutional gatekeeper skepticism and independent research should be familiar with. He is also a regular commenter on Wuwt, and he becomes a fan of what we do.

I first went through some of his in Radio Shack stores (e.g. Engineer's mini notebook and Getting started with electronic products. I still have two.

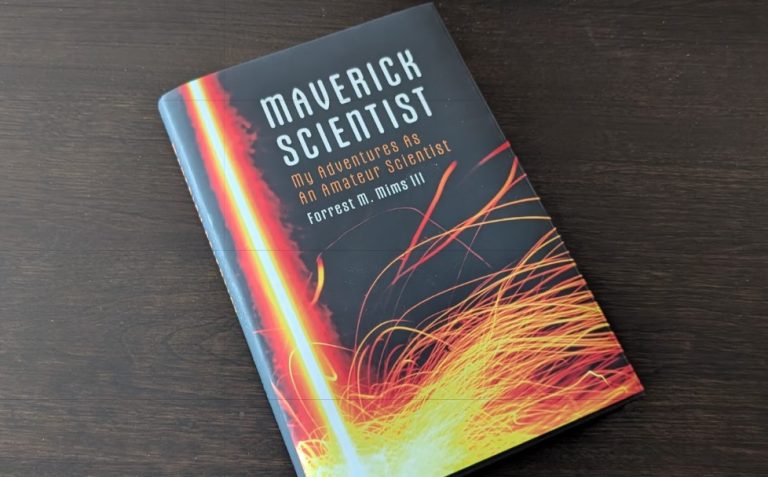

His latest book, Maverick scientist(Finished on Amazon) is both an autobiographical account and a proof of observation of scientific value, and is increasingly overlooked in today's model-driven world of speculation and institutional orthodox.

Despite the lack of a formal academic certificate, MIMS is known for its work in electronic and atmospheric science. He is right Scientific Americanespecially his Amateur scientist Column (back to the magazine is actually about science), his pioneering role in developing scientific instruments makes him a fascinating figure in the history of independent research. But perhaps most notably, he notoriously denies it Scientific American Because of his religious beliefs, this is a stark example of prejudice that exudes “objective” scientific institutions. This book delves into that episode and many other things, and it's a strong reason why science should be open to everyone, not just those with the right certificate or ideological qualification.

Life of scientific inquiry

MIMS tells his lifelong passion for experiments, from young children's tinkering to pioneering research in atmospheric science. His journey included designing altimeters for model rockets, inventing the equipment used by NASA, and (perhaps most relevant to today's discussion of climate), he used simple but effective optical instruments to measure atmospheric aerosols and ozone.

His research, especially on atmospheric turbidity and the effects of volcanic eruptions on solar radiation, highlights an important lesson: Most climate science depends on direct real-world observations, not just theoretical models. MIMS shows that relatively cheap tools can be used to collect critical atmospheric data, undermining mainstream insistence that only large-scale, government-funded research projects are legal.

I think the best part of this book is the design part about atmospheric optics and its LED photometer

One of the most fascinating parts Maverick scientist It is a pioneering work of MIMS and LED photometers, which he uses to measure aerosols, water vapor and ozone in the atmosphere. Compared to traditional scientific instruments, a highly efficient and affordable alternative is developed using simple light emitting diodes (LEDs).

The core principle behind his LED photometer is very simple and clever. When used in reverse, the LED can be used as a narrowband light detector. Each LED is sensitive to a specific wavelength range, so that atmospheric components such as aerosols and ozone can be measured by analyzing sunlight absorbed or spread at different wavelengths. By calibrating these devices and comparing them to more expensive commercial instruments, MIMS proves that his low-cost approach is very accurate, but more importantly, almost anyone can build and use.

He conducted decades of experiments to produce valuable insights into atmospheric transparency, sun darkening and aerosol concentrations. One of his most eye-catching findings involves the effects of volcanic eruptions tracking atmospheric clarity, such as Mount Pinatubo in 1991. He recorded how aerosols ejected into the stratosphere resulted in a substantial reduction in solar radiation reaching the Earth's surface, a well-known but often insufficient natural factor that influences climate change.

MIMS's photometer also enables him to measure changes in atmospheric water vapor, a often overlooked but critical factor in climate science. Unlike carbon dioxide, water vapor is the most important greenhouse gas in the Earth's atmosphere, but the variability of climate models and role in cloud formation remains poor. MIMS’s work provides a valuable empirical dataset that challenges some of the overconfidence assumptions in climate modeling, especially in terms of feedback mechanisms.

He wrote on his Facebook page:

35 years of measuring the sky

On February 5, 1990, I started using homemade instruments to make almost daily measurements of the ozone layer, total water vapor, and the depth of the sky caused by dust, smoke and air pollution. The latter two measurements were performed with the first LED solar photometer, which worked the same way as it was 35 years ago.

You can see all its 35-year data nearby. Note that these two surrounding areas show the impact of the historical outbreak of Pinatubo Mountain in 1991, and the historic underwater eruption of Hunga Tonga in 2022.

The Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (Bulletin) describes the initial 30 years and multiple figures in “The Optical Depth of Aerosols and Total Climate of Total Column Water Vapor and Ozone in Texas (1990-2020).

Note the slight downward trend in the chart. He wrote in the abstract of the paper (bold mine):

The reduction in air pollution caused the average AOD (atmospheric optical depth) to drop from 0.175 to 0.14. The AOD trend has been measured for 30 years with a light emitting diode (LED) solar photometer, the first trend of its kind, similar to the 20-year trend of the modified Microtops II measurement. Although TPW (total pre-water) reacts to El Niño-South oscillation conditions TPW has not shown any trend in 30 years.

The TPW lack trend blows a hole in which climate change leads to a positive water vapor feedback effect. For climate models, so much.

What makes this study so important is not only scientific insights, but also the broader implication: high-quality atmospheric data can be collected without millions of dollars in government grants or institutional approval. This democratization of scientific tools is established by little recognition because it undermines The monopoly they have Excessive climate data and explanations.

One of the book’s most compelling themes is the tension between independent scientists and scientific institutions. MIMS does not shy away from discussing how institutional science often refutes the contribution of “outsiders” even if their data and methods are justified. His own exclusion Scientific American is a good example, but the broader implication is obvious: scientific consensus is often shaped by social and political pressure rather than pure empirical evidence.

In climate science, this is a subject I have observed time and time again. Researchers who challenge the universal narrative (whether in the role of temperature reconstruction, climate sensitivity, or natural variability) are often demeaned and regretted, not because their data are flawed, but because their conclusions do not match orthodoxy. The MIMS story reinforces the need for truly open scientific discourses, in which concepts are tested with ideological reasons rather than being suppressed.

In an age where climate science is increasingly measured by models rather than real-world conditions, MIMS’s work on atmospheric optics is particularly relevant. His efforts to develop solar photometers and track atmospheric aerosol content highlight a key point: empirical observation remains the basis of good science.

For example, MIMS's research on Wall's atmospheric effects provides key insights into how natural events affect climate. This is a crucial opposite for alarmers to claim that all observed climate change is man-made. If a single volcanic eruption can significantly alter atmospheric conditions over the years, what impact does this have on climate models that usually cannot explain this variability?

Maverick scientist This is an inspiring reading for those who believe in the power of independent inquiry. This is especially important for those of us who question the universal narrative of climate science and other politically rife with political science. MIMS embodies the spirit of open, empirical research, which increasingly tends toward conclusions of institutional control and political convenience.

His book also reminds you that science is not the exclusive area of PHD working in government-funded institutions. Some of the most important findings come from people outside the institution – Galilia, Tesla, and now, in the modern era, independent researchers like MIMS. His story is the appeal of amateur scientists, skeptics, and anyone willing to challenge dogma with data.

The final thought

mims' Maverick scientist It’s a refreshing book when scientific debates are often suffocated by institutional gatekeepers. It highlights the value of observation science, the dangers of ideological integration, and the enduring power of curiosity-driven research.

His story of LED photometer alone is worth reading – this is a great example of simple, cost-effective scientific tools that can provide critical data, thus challenging assumptions that are common in climate science. This empirical work, rather than speculative modeling, is the science that should be built.

This book is a must-read for those who think science should be an open inquiry rather than a rigid orthodox concept. It is a tribute to independent thinking, a criticism of scientific elitism, and a guide for anyone who wants to pursue true science – not qualified.

Anthony's rating: 1 in 5

Rewards Comment: Another book he worked at the Mauna Loa Observatory

For readers interested in atmospheric science Maverick scientist It's nice to pair with another Mims book, United States: Global Laboratories in Hawaii. This work records his time study at the famous atmospheric monitoring station on the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii, where key climate and atmospheric measurements (including the famous Keeling curve tracking Co₂ concentration).

exist People in societyMIMS details how he used an LED photometer to monitor the optical thickness of aerosols, a crucial measurement of atmospheric clarity that affects solar radiation reaching the surface. His discovery at Mauna Loa strengthened his early discovery of volcanic aerosols, confirming their significant impact on global temperature fluctuations. Importantly, his work also raises questions about inconsistencies in mainstream climate data collection, especially on long-term atmospheric trends. By showing that affordable, independent tools can match or even exceed expensive government-funded systems, MIMS once again emphasizes the value of empirical science to institutionalized gatekeepers.

His experience at Mauna Loa further illustrates one of the key themes Maverick scientist: Independent researchers can and do make important contributions to science in ways that challenge universal consensus. His atmospheric observations remind people that natural variability (such as volcanic activity and solar radiation fluctuations) plays an important role in climate, which many model-based climate predictions tend to underestimate many model-based climate predictions.

Related

Discover more from Watt?

Subscribe to send the latest posts to your email.