Every summer, as mosquitoes begin to buzz, the risk of the West Nile virus quietly rises—cities are not immune.

In 2012, it burned through the park city, and two wealthy cities were surrounded by the city of Dallas, causing 225 West Nile fever cases, 173 cases of disease had a more severe form of nerve attack, and 19 deaths.

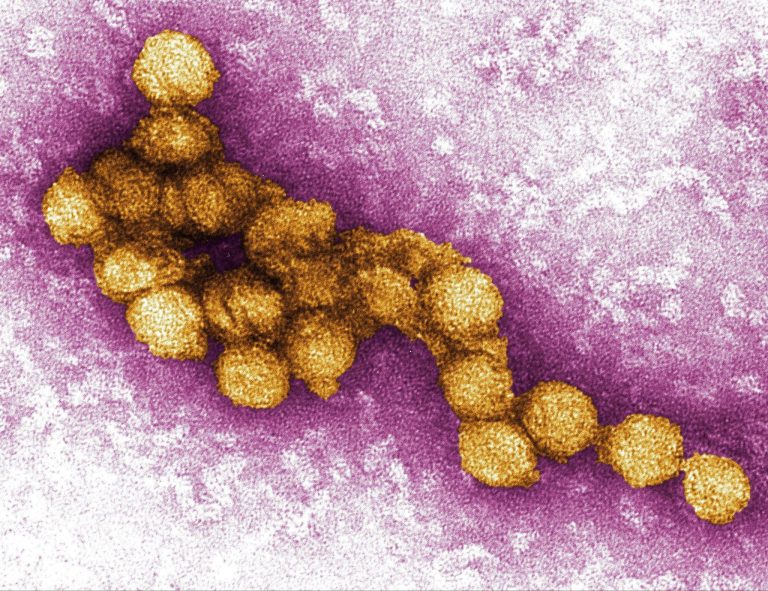

In the United States, the West Nile virus is most commonly transmitted by Culex mosquito species such as Culex Pipiens and Culex Quinquefasciatus. About 80% of people infected with the West Nile virus will not experience any symptoms. However, about one in five people experience fever with flu-like symptoms, and about 150 people develop severe neurological disorders such as encephalitis or meningitis, which can lead to paralysis and death.

Although many may consider mosquito-transmitted diseases to be a concern for tropical or rural landscapes, West Nile virus cases have been found in every state in the United States, with the highest infection rates in Great Plains. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, major cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago and Dallas-Fort Worth have the most cases.

What helps the virus-infected mosquitoes survive and thrive in urban areas? Dr. Robert Haley, an infectious disease expert at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, spoke about the promotion of the West Nile outbreak in urban areas that could stop them and what is expected to increase warming.

This interview has been edited to be clear and length.

Yale Climate Connection: How does the West Nile spread?

Dr. Robert Haley: There are several types of Culex mosquitoes. The West Nile is spreading [in Dallas] A species of mosquitoes called Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes – also known as [Southern] House mosquito. Culex Quinquefasciatus lives around the house – they breed with water filled with water, drains, water-over lawns and anything of any kind that is raised around your house, and they are not far apart.

It creates epidemics in birds, birds and mosquitoes pass back and forth, and if you have all the right conditions to have a significant year, then the epidemic in birds-Maskito will become huge and spill into humans.

YCC: What are the conditions that contribute to these big years?

Haley: We have studied the number of West Nile neurological cases over about 12 years and we found that the biggest determinant is the particularly warm years of winter, with very few days of freezing and substantial rainfall. The warm, humid winters cause the virus to expand in the early summer, so in the midsummer era you start sporadicating mosquito bites, and then you start seeing cases in the mid- to summer situations.

We found [Culex quinquefasciatus] Inclined to [responsible for] Urban outbreaks, not rural outbreaks, you will have a hot spot in different urban areas. We have a hot spot in the heart of Dallas’ wealthiest residential area.

[Park Cities are] Just north of downtown Dallas. Like many downtowns, downtowns just converge buildings and concrete, so that's what's called a heat island. In downtown Dallas, it is always warmer than in the northern area with more wood, houses and lawns. In summer, when transmission occurs, prevailing winds come from the south and southeast. [of Park Cities]. So this actually makes it warmer than the surrounding area. There are hot spots in Chicago, Los Angeles and Sacramento and we know where they are having problems.

YCC: I live in the northwest corner of Chicago and about eight years ago I had West Nile meningitis. I spent a lot of time here in the community garden and spent a lot of time outside, but I think when we were going to hike in the forest reserve we would be worried about these mosquitoes or we were doing something similar but not necessarily around the home. So it's a city problem and it's important for people because I don't think most of our listeners consider these outbreaks that are happening in these cities. For example, everyone I have mentioned likes: “Oh, in Chicago, where do you travel? Have you gone to some exotic place?”

Haley: [The northwest corner of Chicago] It's a hot topic. It is thought that would be poor people, low-income communities and people, because many diseases do gather among people with lower incomes, but the West Nile is [also] The disease of the rich is because it occurs in these areas with high housing density, high property value, large housing, but there is very little open space between the two.

It has just begun, too. The West Nile never happened in this country until it came to New York in 1999, and it reached the Midwest – Chicago and Dallas – 2002. We had some cases every year and then in 2006, we had what we thought was a big epidemic [in Dallas]but in 2012 we had mothers of all epidemics. This is a tragedy.

YCC: What are your advice as a doctor to protect yourself?

Haley: Individuals can try to avoid being bitten by mosquitoes, but it's just so helpful. You can wear an insect repellent and avoid going out in the morning and morning because that is when the Kulex mosquitoes are more likely to bite.

Editor’s Note: Other recommendations include wearing a long-sleeved shirt and long trousers when outside, draining around the house, and placing doors and windows covering or closing to keep mosquitoes outside.

Haley: However, the best way is to have a good public health system in the area, as a good public health system can perform mosquito surveillance. They can put mosquito traps throughout the city like we did in Dallas and trap mosquitoes.

From mosquito surveillance, the health department can calculate what we call mosquito abundance. There have been many mosquitoes over the years, so is it a year or a very small year in the number of mosquitoes? The other is the mosquito infection rate – how many mosquitoes are there? None of these predicts the epidemic. But if you multiply [the number of mosquitoes by the mosquito infection rate]you can estimate the number of infected mosquitoes. We found that this statistics (vector index) can be predicted well and is key to predicting epidemics. When the number of mosquitoes and the number of infected mosquitoes reaches a certain level, we know we are ready for the outbreak. You can then spray mosquitoes in the area where they live with safe insecticides, and you can interrupt or even preempt the epidemic.

Antenna spray is obviously effective. We compared the number of West Nile cases in the sprayed area with the unsprayed area. And you will find this epidemic lasts longer without spraying. The spray will cut it off immediately – you will never see anything again after spraying. The air spray killed very tall mosquitoes, but they multiplied by reproduction within two weeks, but the infected mosquitoes are back and cannot maintain the epidemic in birds and humans. Therefore, spraying doesn't eliminate all mosquitoes, it just stirs them temporarily. But that's enough to end the pandemic.

The ground spray sprayed from the truck is the same spray and is safe, but Culex [quinquefasciatus] Mosquitoes live on top of trees. They mainly eat blood meals with birds – which is where the birds are located – so mosquitoes live with birds on top of the trees. So, with the ground spray, you won't get the top of the tree.

Found it very safe. It will only kill mosquitoes; it won't kill bumblebees or bees, nor will it [harm] people.

YCC: As the climate warms, how do you expect increased risk to the West Nile?

Haley: Increased warmth in any biological system will speed up many processes. For example, in warm weather, viruses grow faster in mosquitoes, birds and humans. In warm weather, mosquitoes bite people more frequently. So, as the weather gets warmer, these conditions will become more common and we will have fewer hard freezing days, meaning these epidemics will become more common.