Climate change and decline in biodiversity are the two biggest environmental crises facing humanity today, but predicting how they will play together is tricky. Ideally, scientists would study how life on Earth responds to sharp changes in previous climate change, but the fossil record of most species is spots.

But the fossils of foraminifera are an exception: they are everywhere.

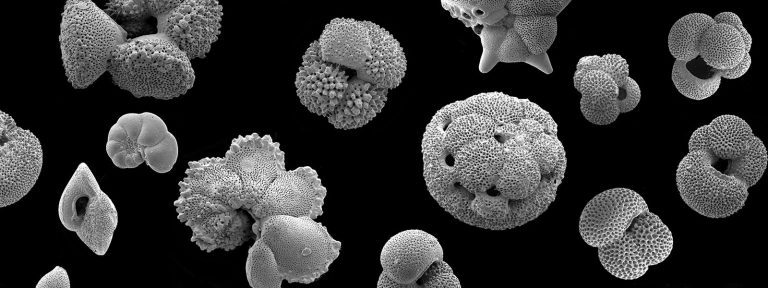

These single-celled marine organisms are encased in shells that are usually made of calcium carbonate, which is the main component of chalk (the main component of chalk (the shells of foraminifera and other organisms that rain under the sea after death). Their name comes from Latin, and refers to the holes connecting different chambers in their often beautiful shells. A series of extended conditions protruding around the shell enables them to find and collect food.

“When you look at a living Form, it's like a tiny trunk of sand, with a lot of tentacles around it,” said Chris Lowery, an ancient journalist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Most species with pores live on the seabed, but paleontologists are particularly interested in plankton species that live in open water. Due to their numbers and short life span, their fossils are spread all over the seabed worldwide.

This allows researchers to reconstruct in detail which species flourished in the past and which species were reconstructed by studying shells and the chemical cues they contained in when climate change. “If you do a little chemistry on the Form shell, you can rebuild things like water temperature,” said Andy Fraass, a microsales scientist at the University of Victoria, Canada. “So, they can tell us a lot about the state of the ocean.”

The researchers studied fossils by drilling into marine sediments to reveal the layers of calcified shells. The deeper they are, the more timely they look back. “You can pull a tube of mud from the bottom of the sea and sample it along its length, each containing thousands of Confucius: detailed records of local history,” Lowery said.

Extinction of mass

This work helps reveal that the plankton foraminifers first appeared about the Jurassic period, and it experienced a major crisis about 180 million years ago when asteroids struck Earth about 66 million years ago. Paul Pearson, a micro-remlinologist at University College London, said: “Everyone is talking about dinosaurs that were extinct at the time, but we know the details of what happened to Foram Fossils. First, there are a lot, and then a unique layer is formed after the impact, and [then there are] Very few after that. ”

The impact rocks release a large amount of sulfur and dust into the air. “That was smoking in a fire for years, blocking the sun for years,” Lori said. “This prevents photosynthesis of algae at the bottom of the marine food chain and causes many ecosystems to collapse.” Deep house foraminifera that are far away from the surface and able to continue to feed on the remains of dead creatures are mostly good, but of 10 scattered species, nine are extinct.

After mass extinction, Fraass and Lowery reported in 2019 that foraminifer species diversity has recovered for about 10 million years. “When the species went extinct, it seemed like a large branch of their family tree had broken down,” Fraass said. “And it takes a lot of time to redevelop enough diversity to allow branches to regenerate.”

However, for those who survived the massacre, this creates opportunities. “With so many species disappearing, competition for previous rare resources has decreased, and even anomalies may have shots, perhaps surprising success.”

Shortly after the impact, Pearson said a new type of foraminifera appeared, “The sting may help them float and capture more food.”

Hot and cold

While the amount of occlusion on asteroids has resulted in a severe cooling period, the next big crisis sounds more familiar: Average temperatures on Earth rose by 5 degrees Celsius about 56 million years ago, possibly due to greenhouse gas emissions caused by volcanic activity.

Foraminifera in deep waters are hit hard, probably due to high levels of CO2 Entering the ocean can cause acidification to damage its calcified shell – this effect is the greatest in the deep. But this time, few surfing species have become extinct, partly because foramen escaped warmth by moving to colder areas.

The history of climate change provides clues to the future of the planet

“In tropical areas, with water temperatures as high as 40 degrees Celsius, they may have been too hot to survive,” Az said. “But we have seen many tropical species appear in more temperate areas, and temperate species are now moving again.” Many foraminifers have found shelters in or near the Southern Ocean region near the Antarctic.

Another mass extinction began 33.9 million years ago, due to a sharp drop in temperature during the transition period called the Eocene-Eocene. This heralds a gradual cooling that reached its climax in the recent Ice Age. “We joked about the Oligocene as the Ugly New Century.” All the weird and wonderful floating foraminifers disappeared, only some small innocents. “We’re not sure why.”

As before, this great crisis created huge opportunities for new species to develop with new habits and habitats. Currents originating from poles lead to temperature differences between oceanic layers that peak near the equator. This creates a wider range of conditions that support a wide variety of species.

In a 2023 study, Aze and others showed that around 15 million years ago, the global spread of foraminiferous diversity became roughly what it is now – the largest near the equator and gradually lowered the pole.

An uncertain future

These past events tell us what we expect today foraminiferous diversity and other species on a planet we are rapidly warming today?

In a 2023 study, Pearson and colleagues used fossil data with holes to predict the fate of the ocean’s twilight zone, which is an area below 200 to 1,000 meters. They estimate that food supply to the middle of the region will drop by more than 20% in the case of mild warming, in which case the global average surface temperature rise remains below 2 degrees Celsius and a 70% drop when the temperature is unlikely to rise by 2100. This is because warm-up increases the decline rate of falling organics, so it is so.

This could cause damage in this vast and studied part of the world, providing vital habitats for many marine animals that are snorkeling for prey, as well as unique species like the unique species that fall during the day.

Aze said organisms have moved mountains in response to global warming, and step by step, scientists have noticed a decline in diversity of foraminifers around the equator. “That might expand,” she said.

Although some species may be moving towards the poles, the pace of climate change may be too fast for many. A 2024 study on foraminiferous trends found that foraminiferous abundance has dropped by nearly 25% over the past 80 years.

This may be a bad sign of biodiversity in other biota, which often follow the trend of foraminifera. Fras said that because foramen bounced from several mass extinctions as a group, they were unlikely to disappear. But recovery can take a long time, and human involvement makes predictions of the near future particularly difficult. Or as Lowery said: “Ask me again for thousands of years.”

This article first appeared in a well-known magazine,,,,, A nonprofit publication dedicated to scientific knowledge that is accessible to all. Sign up for newsletters for knowable magazines.