pass Grist and WBEZa public radio station that serves the Chicago metropolitan area.

The grasslands in America are so huge and so strange that they destroy understanding.

Newcomers of seemingly endless grasslands once crossed about a quarter of North America, often hitting the psychological wall and falling into mania. This phenomenon is well known that the madness of the prairie was recorded by journalist EV Smalley in 1893, after a decade of observation of life at the border: “Among the peasants and their wives, the new prairie country has had a shocking insanity.”

The treeless, isolated expansion of the United States put the early settlers in Europe to test. Drought, loneliness and debt drive many people to fail, forcing homestay families to retreat.

But those who stayed carried out one of the largest terrain projects in history, rewiring the land, climate and the future of the continent.

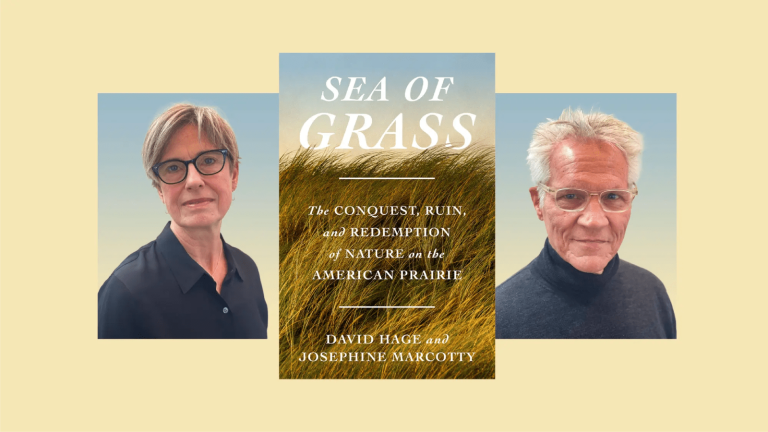

exist Grass Sea: Conquest, Ruins and Redemption of Nature on American Prairielongtime Minnesota journalists Dave Hage and Josephine Marcotty tracked this amazing transformation. “They colonized North America in the 19th century, Europeans who completely changed the hydrology of the continent like glaciers,” they wrote. “But it's worth noting that they're not thousands in less than 100 years.”

When putting hundreds of millions of acres of prairie onto the plow, settlers not only forcibly replaced the indigenous countries, but also completely changed the ancient carbon and nitrogen cycles of the region. They also turned the region into an agricultural powerhouse. Dark black soils once prevalent in the Midwest, the result of thousands of years of animal and plant decomposition that deposit countless carbon storage into the ground – the foundation of modern food systems. But the removal of the American grasslands also removed one of the most effective climate defenses on the planet.

Grass, like all plant life, inhales planetary carbon dioxide. As a result, “Earth’s soil now contains one-third of the Earth’s land carbon – more than the total human activity since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.” A 2020 natural study found that since the 1800s, only 15% of the world’s plowed grasslands can absorb nearly one-third of humans.

Today, most of the Targrass Prairie covering Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and the Far Eastern edge of the plains, accounting for about 1% of its previous range. Even the harder grasslands in the western United States have been reduced by more than half.

“This is the paradox of the grassland,” the author wrote. “The North American prairie is one of the richest ecosystems.

At that time, Americans were trying to understand the prairie. Hage and Martcotty talked to Grist about the near collapse of the American grasslands, what its return would mean in a rapidly warming climate era.

For clarity, this interview has been condensed and edited.

The reason for our own danger is misunderstood. Why is this why, how do you make people care about grass?

Josephine Marcotty: When European settlers first arrived, they were frightened by the open space and the crazy weather they encountered on the grassland. The wide grasslands were not something they experienced in Europe, which was much more controlled by humans for a longer period of time.

David Hage: These areas are so far away, many of which are immigrants from sweet little villages in Norway, Sweden or Germany. They landed here and they probably don't have neighbors within 10 or 15 miles. People do suffer from terrible loneliness and even mental illness due to isolation.

JM: But when Americans realized that the grassland was something to be preserved, the Targras grassland almost disappeared. It was cultivated and turned into farmland. So the Targras Prairie is something we have never experienced before. We don't know what this is.

DH: We can talk about wildlife, we can talk about water, L, but what shocked me is climate change. The world's grasslands are one of the largest buffers for the defense of climate change on Earth. When we cultivate grassland, like we do now, one million acres per year, you will release a lot of carbon to make climate change worse, and you are taking out all the grass that may be isolated in the future. A researcher we spoke with Tyler Lark of the University of Wisconsin said the latest tillage rate in Western grassland farming is the climate change that adds 11 million cars to the road each year. So, this is a climate change disaster.

Early settlers not only cultivated grasslands. They also forcibly replaced the indigenous peoples to do so. How do you view large-scale prairie restoration as a form of compensation?

DM: We wrote about the Bison Herds of the West during the Native American Retention. There are now 25 or 30 of these wonderful herds of bison cattle. The operation to rescue Yellowstone Bison and distribute it to the Natives has launched these tribal bisons from Alaska to Texas. This is two-thirds of the victory: it saves this endangered magnificent animal; it is good for the grassland, because grazing in the wilderness and grass breeding. This is a wonderful way to preserve the threatening cultural heritage of the South Dakota plain tribes. There is also a great outfit called the Buffalo Meadow Alliance, a tribal action designed to raise funds to restore grasslands and local ecosystems on tribal-managed land.

JM: Many tribes have a sacred herd of cattle that are used in cultural and religious rituals, and they also have herds of livestock that they use to turn into meat they sell, not only to members of the tribe, but to others. It is this economic independence that gives a stronger sense of sovereignty. Without economics, you can't do it.

Most of the grasslands disappeared. Given its value, why is its destruction continuing? Is it a policy, profit or something else?

JM: Because corn pays more than cattle or bison.

DH: We encountered an amazing statistic where the prairie was the last to get the statistics of its own national park in all major landscapes in the United States. It didn't happen until 30 or 40 years ago, one of the reasons was to protect that grass, and they would compete with farmers and people who wanted to make a living on this land.

JM: EPA has just improved its ethanol fuel mission. In other words, they create a larger market for corn. It is ethanol that has really raised corn prices since we started forcibly using ethanol in fuels. This will continue as long as we don’t subsidize other farmers who actually grow food for us. Otherwise, the grassland will never be able to compete.

The book shows that federal subsidies for ethanol have caused catastrophic disasters to the grassland. Can systems that are both ecologically catastrophic and economical can be demolished?

DH: It is a huge source of income for upper-class farmers in the Midwest. We met a lot of farmers who said, “If it weren’t for ethanol, I wouldn’t be able to sell my corn crop” or “I didn’t make money until after ethanol came out.” So it’s hard for politicians running in the Midwest to stand up with ethanol. But this will only make a very moderate change to the Federal Farm Act: the task of reducing the ethanol slightly, adding more money to these proven federal protection programs that reward farmers for their conservation habits on working land.

JM: Economics is a false economy. It's all driven by federal policy rather than markets.

DH: In the process of reporting on the book, we met great people – generous, hard-working people – but they were trapped in the system they made. We have this set of federal subsidies that only push farmers to farm more land, grow more corn, use more chemicals, and have no choice if they want to save the family farm and keep it open.

This book has an alternative vision of agriculture that can save soil and may even provide lifelines for grasslands. What is that and where does it happen?

JM: No matter where you farm, things will be different. It is much easier to grow crops in southern Iowa than in North Dakota, simply because of the weather differences. One big thing here is that farmers grow more crops. Nature doesn't like simplicity. Nature loves complexity, and if we have a more complex farm system, it would be better for everyone.

DH: Research from Iowa State University and the University of Minnesota is very good, which shows that when your crop rotations are slightly diversified, you have less flooding, less erosion, healthier soil, less diesel fuel and less fossil fuel fertilizer.

Originally published by Grist, the story is part of Climate Now, a global news collaboration that enhances the reporting of climate stories.